Global Financial Governance & Impact Report 2013: FSB

FSB Governance

Author: Eric Helleiner, University of Waterloo

The Financial Stability Board (FSB) is the newest addition to the group of international institutions concerned with global economic governance. It is not entirely new, however, because the FSB is really a successor to an earlier body – the Financial Stability Forum (FSF) – that was created by the G7 countries in 1999 to foster international financial stability. The FSF was designed to facilitate coordination among various national and international financial authorities, and to assess vulnerabilities and oversee actions needed to address them, including the development and implementation of international financial standards. In the wake of the East Asian crisis of 1997-98, the latter task was deemed particularly important by G7 policymakers who hoped worldwide compliance with international financial standards would create a “new international financial architecture” that would be less crisis-prone.

The outbreak of a new global financial crisis in 2007 highlighted the failure of that goal in a rather spectacular way. Indeed, despite its ambitious mandate, the FSF had played a very low key role in global financial governance between 1999 and 2007. The FSB’s creation in 2009 represented an explicit effort to create a stronger and more effective body to promote global financial stability. The FSB was described early on by US Treasury Secretary Geithner as “in effect, a fourth pillar” of the global economic architecture alongside the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank (WB) and World Trade Organization (WTO). But its governance is very distinctive vis-à-vis those other institutions, raising a number of unique challenges. Some of these challenges are being addressed, but many significant ones remain.

Membership and Inclusion

The first challenge concerns the FSB’s membership. Following the FSF’s model, the FSB’s membership includes a number of other international bodies, such as the IMF, WB, OECD, Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the Committee on Global Financial System (CGFS) as well as various international financial standard-setting bodies (SSBs) that have been created since the 1970s. The FSB’s country membership is also much more exclusive than that of the IMF, WB and WTO, including just the G20 countries, Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Singapore, Switzerland, Spain as well as the European Commission and European Central Bank. This membership is in fact wider than that of the FSF (which, in 2007, had included just the G7, Australia, Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Singapore, and Switzerland). Even with this expansion, however, a very large number of countries still remain “outsiders” to the institution, affected by its deliberations without having much say in them. Indeed, the FSB has openly acknowledged the problem that many of the new international financial standards it is promoting have unintended consequences for non-members.

Partly to address this problem, the FSB has established six regional consultative groups (RCGs) for the following regions of the world: Americas, Asia, Commonwealth of Independent States, Europe, Middle East and North Africa, and Sub-Saharan Africa. These RCGs began meeting in late 2011 and each includes both members and non-members. They are designed to encourage greater dialogue between the two groups and approximately seventy non-member jurisdictions are participating in them. Some documents being discussed in the Plenary meetings, but not yet made public, are shared with the RCGs for consultation, and recommendations and papers of the latter are reported back and circulated to the FSB’s Plenary. The RCGs are co-chaired by a member and non-member, and the latter participates in the FSB Plenary as an observer.

The role of the RCGs in providing voice for non-members of the FSB could be enhanced in a number of ways in the short-term. First, the FSB should be required to provide feedback on RCG recommendations. Second, non-members should be given a larger role in the FSB’s decision-making. For example, the non-member co-chairs of the RCGs should be given full membership in the FSB Plenary, while other non-members could be invited on a more regular basis as observers and serve as more active participants in the FSB’s various working groups, task forces and committees. Third, the RCGs could be strengthened through the provision of secretariats located in their respective regions. And finally, the FSB could do more to clarify the process of selecting invitees to the RCGs as well as to strengthen its efforts to engage in outreach to countries not included in the RCGs (as it is mandated to do under its 2012 charter).

While these initiatives would be useful, the longer-term goal should be to create a FSB with more universal membership. In the late 1990s, some proponents of the FSF’s creation had urged for much wider membership of this kind for that body. Canada’s finance minister at the time, Paul Martin, made the case in the following way in the summer of 1999: “it is not reasonable to expect sovereign governments to follow rules and practices that are ‘forced’ on them by a process in which they did not participate. Therefore, whatever form the renewed global financial architecture ultimately takes, all countries must ‘buy into it’ and take ownership. Only then will the framework have legitimacy.” The same logic applies today.

One possible objection to larger FSB membership is that the FSB’s charter requires that members make certain commitments relating to issues such as: the openness and transparency of the financial sector; the implementation of international financial standards; and participation in IMF/World Bank Financial Sector Assessment Programs (FSAPs). Would non-members be willing to make these commitments? The question cannot be answered without first inviting all non-member jurisdictions to consider membership.

Another common objection is that a large membership would make discussions unmanageable in the FSB’s Plenary (which serves as the institution’s sole decision-making body and which operates according to a consensus rule). But this problem could be addressed through the use of a constituency system similar to that used in the IMF and WB. The FSB has already accepted the principle that member countries are not all allocated the same numbers of seats in the FSB’s Plenary. Some countries – the G7, Brazil, China, India, and Russia – are represented by three officials from their respective central banks, finance ministries and supervisory authorities. Others – Australia, Mexico, the Netherlands, South Korea, Spain, and Switzerland – have two representatives, while the rest (Argentina, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Singapore, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Turkey) have just one. Introducing a constituency system would represent a further step along this line.

Transparency and Accountability

The FSB’s governance would also be improved with greater transparency and accountability. The FSB has already made some improvements over the FSF in these areas. The G7 gave the latter a very general mandate and its activities were often obscure. By contrast, the FSB was established with a formal charter that outlined in detailed fashion the core mandate of the institution as well as its structure. In June 2012, this charter was revised to include a new section titled “accountability and transparency.” That section notes that “the FSB will discharge its accountability, beyond its members, through publication of reports and, in particular, through periodical reporting of progress in its work to the Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors of the Group of Twenty, and to Heads of State and Governments of the Group of Twenty.” In keeping with this directive, the FSB has established a website which includes its various reports, and the FSB provides detailed progress reports to the G20.

The FSB could do more, however, to improve the institution’s transparency and accountability to the general public. The FSB still does not release much information to the general public about its meetings, including those of its Plenary and the RCGs. An important initiative would be to make public all meeting schedules, agendas, attendees, and minutes of meetings of the Plenary and RCGs. Greater transparency could also be achieved by the release of more documents being discussed in these meetings and other FSB groups. The FSB Secretariat’s communication with the general public could also be improved, including through the listing of more staff contact information on its website.

Greater transparency to the general public may help to reduce the risk of the “capture” of international financial standard setting processes by private sector actors. There has been much speculation in the media and among scholars about how this kind of capture may have contributed to lax regulation at the national and international level during the years leading up to the 2007-08 crisis. The importance of minimizing the risk of private capture has only been heightened by the post-crisis emphasis on “macroprudential” regulation that requires financial authorities to take a strong stand in counteracting market trends, such as cyclical booms or growing concentration and risk-taking within the financial system. Transparency can also help to reduce the risk of capture by encouraging greater public engagement in the FSB’s activities in ways that offset the potential influence of private sector groups (which often have greater access to the policymakers).

In fact, the wording of the FSB’s initial 2009 charter in fact seemed to confirm the privileged access of private sector groups. It stated that, when developing its medium and long-term goals, the FSB would “consult widely amongst its members and with other stakeholders including private sector and non-member authorities.” By restricting its choice of societal actors to the “private sector,” the FSB left itself open immediately to the charge that private financial groups would receive special treatment. This impression was only reinforced in another part of the initial charter which stated: “In the context of specific sessions of the Plenary, the Chair can also invite, after consultation with Members, representatives of the private sector.”

The revised 2012 charter partially responded to this criticism. While retaining those provisions, it added a new line: “The FSB should have a structured process for public consultation on policy proposals.” The FSB has indeed begun to invite public input on proposals. A further step would be to allow civil society organizations to be invited to specific sessions of the Plenary (as is true for private sector representatives) and the RCGs, as well as to provide input into the FSB’s various working groups, task forces, and committees. In a June 2012 report to the G20 leaders, the FSB noted it should also “engage in dialogue with market participants and other stakeholders, including through roundtables, hearings and other appropriate events.” Those other stakeholders should include civil society organizations. More generally, the FSB should also be required to release information on all consultations it holds with the private sector and other societal actors.

The FSB could also improve its accountability to its members. In the first two years of the institution’s existence, there was a widespread perception that the FSB’s influential Steering Committee was dominated by central bankers, particularly those from advanced industrial countries. Prompted by the G20 leaders, the Committee’s membership was reconstituted and expanded in January 2012 to include representation from the executive branch of the “G20 Troika” countries (the previous, existing and subsequent G20 chairs) and of the five countries whose financial sectors were most systemically important. Geographic regions and financial centers that had not been represented on the Committee were also included. These reforms highlighted the need for greater transparency surrounding the selection process of the membership of the FSB’s various committees, task forces and working groups.

The perception that the FSB is dominated by central bankers has been reinforced by the fact that the central bank-controlled BIS has been hosting the organization, and providing its funding (as well as many of its staff). When new Articles of Association were established for the FSB in January 2013 (see below), an opportunity to change these arrangements arose, but instead, the FSB continued to be located in the BIS and its funding was secured through a multi-year agreement with the BIS. While the latter allows the FSB to be placed on a more firm financial footing, does it make sense from an accountability standpoint to have the organization financially dependent on just one of its members (the BIS)? Wouldn’t the FSB be more accountable to all its members if it was funded instead by a membership fee (an option that was considered but rejected)?

Responsibility and Effectiveness

Perhaps the most serious challenge facing the FSB’s governance is the question of whether it has enough influence to be effective. Unlike the IMF, WB and WTO, the FSB is not a multilateral treaty-based organization. It was created simply by an announcement of the G20 leaders at their second summit meeting in London in April 2009. Although the FSB was given a charter, that document was never ratified by any legislature. The charter also noted very clearly that it was “not intended to create any legal rights or obligations”. Indeed, when it was created, the FSB did not in fact have any formal legal standing.

Just like the FSF, the FSB was thus established as a remarkably toothless organization with no ability to compel its members to abide by its decisions. The problem applies not just to the FSB’s country members but also the IMF, WB and OECD which highlighted that they would not necessarily be bound by FSB’s decisions when they joined the institution. The international standard-setting bodies have also protected their independence. The FSB’s charter notes that it will “undertake joint strategic reviews of and coordinate the policy development work of the international standard setting bodies to ensure their work is timely, coordinated, focused on priorities and addressing gaps.” But the charter goes on to acknowledge that “the standard setting bodies will report to the FSB on their work without prejudice to their existing reporting arrangements or their independence.” [emphasis added]

This weakness of the FSB is compounded by the nature of international financial standards. In contrast to the international trade agreements, these standards have long been non-binding “soft law” with which compliance is entirely voluntary. Like the FSB itself, none of the SSBs that developed these standards were multilateral treaty organizations. They have no formal power and little capacity to encourage compliance. It comes as little surprise that compliance with international financial standards has often been uneven in the past.

As part of its mandate to encourage the implementation of international financial standards, the FSB has been given a few new tools. FSB member countries have agreed to undergo peer reviews as well as participate in FSAPs. In late 2011, the G20 leaders also endorsed a new FSB “coordination framework for implementation monitoring” to encourage implementation of a core group of post-crisis international standards. The framework focuses on the role of enhanced public reporting and monitoring, with the FSB Secretariat producing an annual status report on the progress of countries’ implementation.

These tools and initiatives may help to encourage compliance with international standards, but a more ambitious strategy would be to transform the FSB’s legal status into an organization more like the IMF, WB and WTO. This transformation was considered in 2012, but a multilateral treaty-based organization was deemed then to be “not an appropriate legal form at this juncture”. Instead, a much more limited reform was introduced in January 2013 in which the FSB was given a legal personality as an association under Swiss law. Its new Articles of Association continued to stress that the FSB’s activities and decisions “shall not be binding or give rise to any legal rights or obligations”. Perhaps we will need to wait until the world has experienced one more major crisis before this core weakness of the FSB’s governance will be addressed in a significant way.

FSB Impact

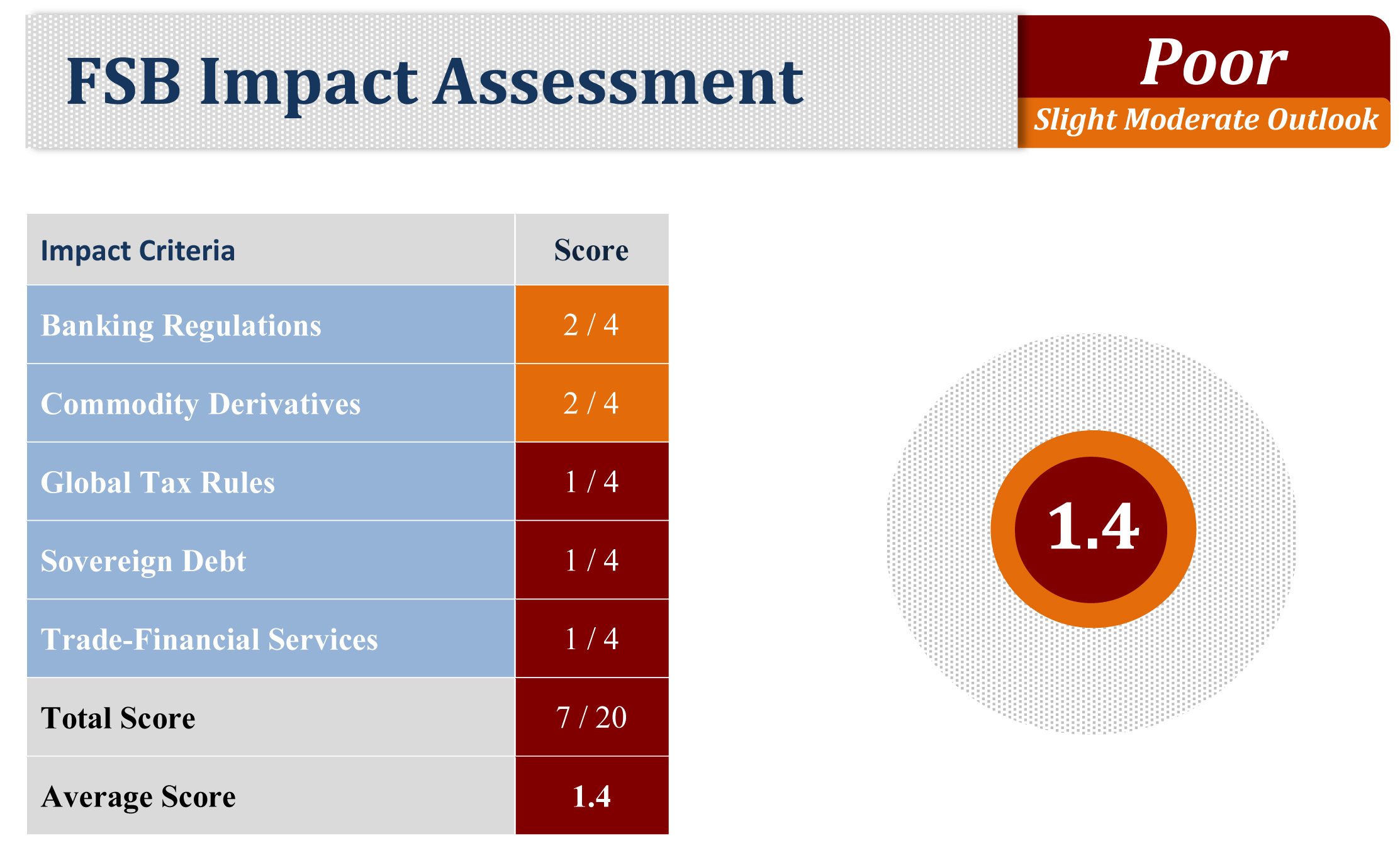

No country – advanced or developing – was completely excluded from the consequences and hardships caused by the 2007-2008 financial crisis. Nonetheless, the reforms, standards and rules for the global financial system are agreed upon in an exclusive institution: the Financial Stability Board. This exclusion is justified by the fact that financial markets – and their regulators – are concentrated in the FSB countries, and the onus of implementing reforms is mostly theirs. Although developing countries may seem to have lesser stake in the global financial system, they are more vulnerable to instability in the global economy – face disproportionate consequences when regulations fail to maintain stability. This section considers the impact of FSB decisions for developing countries, for which some components of the global financial architecture are of particular concern, such as: Banking Regulations, Derivatives Market, Global Tax Rules, Sovereign Debt Markets and Trade and Financial Services. In this section, experts provide a brief assessment of the FSB’s work in each of these areas and how it impacts developing economies, as well as a score based on the “Impact Scorecard.”

Banking Regulations

Authors: Eric Helleiner, University of Waterloo, and Lesley Wentworth, South African Institute for International Affairs (SAIIA)

Why is this issue vital?

To date, the FSB’s bank regulatory agenda has focused primarily on Basel III. The third Basel Accord Framework sets out, inter alia, higher and better-quality capital requirements and a leverage ratio that should result in better risk coverage and reduce the probability and severity of future potential banking crises.

Unfortunately, Basel III only addresses financial institutions with which many people in poor countries have no relationship. Critics also argue that Basel III may have the effect of reducing international financial flows to emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), reinforcing the case to focus more on how local financial institutions can better serve local financial needs.

What should the FSB be doing?

In this context, the FSB should devote more attention to the financial inclusion agenda that has emerged as a central goal of many international and national development institutions, as well as the G20. The exclusion of a significant section of the population in EMDEs from financial services represents a risk to the integrity of the financial system, with much higher potential for financial crimes. This raises a number of issues that are part of the FSB’s financial stability mandate.

As part of this mandate, the FSB should:

- Improve its focus on regulation of financial institutions outside of traditional financial systems and distinguishing between ‘worthy’ community-centered institutions, like community banks vis-à-vis fraudulent and exploitative financial lenders. This is in line with the FSB’s efforts to strengthen oversight and regulation of the “shadow banking” sector.

- Support regulators in discouraging banks from discriminatory practices and focusing on pro-poor inclusivity, such that access to both banking and non-banking financial services is improved.

- Continue to establish fair and equitable standards and foster best practices across this area of focus.

- Encourage research cooperation in this area, especially across FSB Regional Consultative Groups.

Evaluating the FSB’s progress

These recommendations build on the FSB’s February 2012 RCG for Sub-Saharan Africa meeting which identified the need to enhance financial inclusion. They are also in keeping with the FSB’s work on consumer finance protection and the efforts of FSB members to explore options for strengthening consumer protection through the establishment of consumer protection authorities and implementing responsible lending practices.

An encouraging sign is that the FSB is launching a Resolvability Assessment Process in 2014 that will include authorities from countries “hosting” global systemically important financial institutions (G-SIFIs). If this includes EMDEs, beyond just the BRICS, policy outcomes are more likely to benefit developing countries and their citizens that depend on banking services provided by G-SIFIs. *See FSB EMDE Monitoring Note, Sept 12

Commodity Derivatives

Authors: Steve Suppan, Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP), and Peter Wahl, World Economy, Ecology and Development (WEED)

Why is this issue vital?

A major factor contributing to food insecurity in food import dependent Emerging Market and Developing Economies (EMDEs) is excessive speculation in agricultural commodities. Financialization of commodity markets has resulted in price movements and price volatility in commodities beyond what can be explained by real economy factors.

What should the FSB be doing?

The FSB has the mandate to monitor market developments and their effect on regulation. The FSB Over the Counter (OTC) Derivatives Working Group should analyze the effects of deregulation and regulatory avoidance on commodity derivatives prices and price volatility, for example by OTC dealer broker resistance to rules to realize the G-20 mandates.

The FSB should interpret its mandate to include, through evaluation, impacts of the financialization of commodity markets on the real economy. The FSB should study the effects of commodity indexed speculation on food and energy prices and price volatility in EMDEs affecting EMDE financial stability. The FSB OTC Derivatives Working Group and EMDEs Review Group should invite stakeholder input in the design of the study and comments on the consultation and its recommendations.

Evaluating the FSB’s progress

The G-20 members have yet to implement OTC derivatives commitments. The FSB has recognized that better pre- and post-trade data is necessary to regulate markets effectively, and that inconsistent and incomplete reporting will prevent realization of commitments. It has recommended to the G-20 that OTC trade data should be in a standardized format to enable timely and comprehensive surveillance within and across markets. Without such surveillance, effective enforcement and planning for possible new rules cannot be carried out. However, restrictive rules on regulator access to data can frustrate fulfilling the purposes of the FSB’s forthcoming feasibility study on data integration.

FSB summarizes the state of OTC legislation and regulation as reported by G-20 members, but it has not reported even synthetically on how and why implementation of regulation has been frustrated. It has alerted G-20 finance ministers to the potential risks posed by synthetic index derivatives funds. It has yet to advise the G-20 on the consequences of High Frequency Trading, particularly of OTC derivatives, for financial stability.

Sovereign Debt

Authors: Eric LeCompte, Jubilee USA, and Kunibert Raffer, University of Vienna

Why is this issue vital?

Sovereign debts have repeatedly posed threats to financial stability, highlighting severe vulnerabilities of the financial system. While Euro-countries are presently the focus of the debate, new debt crises are brewing in quite a few developing countries. There is an urgent need to prepare for future crises.

Assessing and addressing these vulnerabilities is central to the FSB’s mandate. As regulatory norms were an important cause of most severe debt crises, the problem of sovereign debts demands appropriate regulatory reforms to stabilize the system, i.e. the very activities for which the FSB was created.

What should the FSB be doing?

The FSB must address the problem of sovereign insolvency by working on a sovereign debt procedure that is economically sound, based on the Rule of Law, and renders the system more crisis resistant. The advantages of such a procedure recommended by Adam Smith are proven: all national jurisdictions apply bankruptcy laws to resolve insolvency.

Learning from past sovereign debt crises, an international regulatory framework must be designed. Lower capital weights for potentially destabilizing short term lending and the strong links between capital weights and credit rating agencies have to be reconsidered. Internal risk assessment by the regulated must be abolished. Loan loss provisioning should be more widespread.

Evaluating the FSB’s progress

Regarding sovereign debt vulnerabilities, the FSB has unfortunately not been very active. Regulatory changes to reform Basel II have been made, but they have not sufficiently redressed the problem of undue preference for short-term lending, nor of internal risk assessment. Loan loss provisioning plays a strong role but has yet to be adequately addressed by the FSB. The FSB should support and work to enact the UNCTAD Principles on Responsible Lending and Borrowing. The FSB should use the ratio of debt service paid to debt service due as another possible early-warning indicator of a sovereign debt crisis.

Implementing reforms to mitigate the negative impacts of excess public debt would stabilize sovereign lending and help to defuse future debt crises. The present situation of many developing countries makes this mandatory. In addition, the dependence of the world’s financial system on very few credit rating agencies (CRAs) is problematic, especially for sovereign debt, and should be corrected. According to its own September 2013 Status Report, the FSB has failed to even develop policy recommendations for reducing reliance on CRAs.

Taxation and Illicit Financial Flows

Authors: Soren Ambrose, ActionAid, and John Christensen, Tax Justice Network

Why is this issue vital?

Taxation is crucial for EMDEs as they struggle to expand their development. Domestic resource mobilization provides the highest quality revenue streams for developing countries, both in terms of sustainability and accountability. It facilitates advances toward the end of aid dependence and the avoidance of future debt crises. In addition to providing revenues needed for public services and infrastructure, taxation is also the most practical vehicle for establishing accountability between citizens and the state apparatus. Tax policy is a vital tool, too, for managing ecological risks like climate change by putting a price on destructive actions.

More generally, for the last 30 years or so, global economic structures and trends have been shaped by “financialization” rooted in the manipulation of existing rules in the pursuit of tax arbitrage more than productive economic activity. Global financial stability – and ultimately a healthier form of globalization – requires a shift away from the exploitation of perverse incentives.

What should the FSB be doing?

International tax regulation has long suffered from being subject to partial coverage by a large number of entities, from the OECD to the IMF. But where everyone is in charge, no one is in charge, and jurisdictions are more inclined to engage in a regulatory race to the bottom. If the FSB takes seriously its responsibility to diagnose global financial vulnerabilities and its coordination function, it should intervene to fill the gaps and bring coherence to the multiple actors now attempting to manage the task.

The FSB should assume a coordinating function for tax regulation and perform monitoring of the effectiveness of existing regulation. In keeping with its mandate to identify vulnerabilities, the FSB should also serve as an advance warning agency that can flag the potential for instability resulting from, for example, the widespread use of derivatives for tax arbitrage. It should set standards for minimum levels of transparency, including public registry of ownership information (including trusts, fiduciaries, and foundations).

Evaluating the FSB’s progress

The Financial Stability Forum (FSF) – the FSB’s predecessor – issued a high-quality report from its Working Group on Offshore Centers in April 2000. Since then, we cannot identify much relevant activity. To evaluate future FSB’s progress in this area, attention could focus on criteria such as: improved transparency of ownership information; improved access for non-OECD jurisdictions to automatic information exchange processes; setting standards for international cooperation to counter harmful tax competition; and adoption of accounting standards to enhance corporate transparency.

Trade and Financial Services

Authors: Andrew Cornford, Counseller with the Observatoire de la Finance, and Myriam van der Stichele, Center for Research for Multinational Corporations (SOMO)

Why is this issue vital?

GATS/FTA rules are, in principle, often in contradiction with, and constrain, current financial reforms. The rules of GATS/FTAs facilitate circumvention of financial regulation and its reforms.

Foreign banks are not interested in inclusive finance, which is important everywhere but especially vital in EMDEs. Foreign control of domestic banks in developing countries, which is favored by the rules of the GATS and FTAs, is often an obstacle to policies promoting financial inclusion.

Liberalization of financial services in accordance with GATS/FTA rules increases vulnerability to financial instability from external sources, i.e. the home countries of the foreign banks and international markets.

Controls over the liberalization of trade in financial services through GATS/FTAs are vital because:

- International trade in financial services is capable of undermining global financial stability.

- International trade in financial services institutionalizes the overbearing power of the financial sector.

- Such power can undermine democracy by narrowing the policy space and constraining the implementation of enacted laws on financial regulation.

What should the FSB be doing?

Although the rules of GATS/FTAs are relevant to the introduction and implementation of international standard for financial regulation, they are currently not part of the agenda of the bodies setting international financial standards, a gap that the FSB should address. Particular attention should be devoted to: 1) the deregulation of capital movements under the rules of GATS/FTAs; 2) constraints on, and prevention of, macro-prudential regulations; and 3) measures of cross-border crisis management still largely untested under GATS /FTA rules. Given its mandate to coordinate a wide-range of the financial policies at both the international and national levels, the FSB should include these issues.

Evaluating the FSB’s progress

FSB is not currently addressing the relation between its policy agenda and the rules regarding international trade in financial services of the GATS/FTAs. The FSB’s future impact in this area should be judged according to its eventual willingness to extend the coverage of its agenda to include the GATS/FTA rules on international trade in financial services. In particular, the FSB should proactively identify instances of the incompatibility of the standards for financial sector regulation and other policies that it promotes, on the one hand, and GATS/FTA rules and country commitments in the World Trade Organization (WTO), on the other.

An encouraging sign from the FSB: Transparency in Global Finance: The global Legal Entity Identifier (LEI)

Author: Navin Beekarry, Center for Law, Economics & Finance (C-LEAF)

The financial crisis demonstrated the extreme complexity of the global financial system and that risks can spread rapidly. Lack of accurate identification of legal entities engaged in financial transactions raised significant challenges for regulators and private sector managers responsible for evaluating and mitigating these risks. A Legal Entity Identifier (LEI) system addresses this challenge. An LEI is a unique code that identifies a legally distinct entity that engages in a financial transaction. The Global LEI System (GLEIS) – initiated by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) per the request of the G20 – is designed to be the first global and unique entity identifier with free and open access for regulators, industry, NGOs and the public.

A primary objective of the GLEIS is to help global regulators to better measure and monitor systemic risk across financial entities across jurisdictions. The GLEIS will help regulators in identifying entity, group, business line, or geographical risk concentrations to gain a more complete and accurate picture of risks than ever before. Such a framework will provide a transparent, open and fair system, that protects against the risk of abuse of dominant market positions, and that facilitates quick adoption.

The LEI is also expected to provide greater transparency into the beneficial owners (the person(s) who actually own and reap profits from a trust or corporation) of legal entities (LEs). Relationships data that is compiled by the GLEIS will facilitate the tracking of relationships among LEs, their affiliates across jurisdictions and the ultimate beneficial owner. In the financial collapse or 2008 no one knew Lehman Brothers’ or AIG’s connections. The GLEIS will make it much more difficult to engage in money laundering, tax evasion and other illegal financial transactions. Developing economies, which are disproportionately affected by illicit financial flows, will be a major beneficiary of a global LEI system.

However, as the GLEIS system is by nature a public good, there is a need to make sure that the gains for the broader public are captured and that provision of the GLEIS is not exploited in ways that will harm the public. Incentives for suppliers of the LEI to exploit their privileged position and overcharge registrants, restrict access, cut corners on data quality, or to use a position of privileged access to LEI information to supply other revenue-generating services on non-competitive terms, constitute serious challenges to the public nature of the LEI. These arguments provided the motivation for the FSB mandate to produce recommendations for a governance framework for the LEI that identifies and provides strong protection of the public interest.

The report can be accessed through the attached link: