Global Financial Governance & Impact Report 2014

A GLOBAL FINANCIAL GOVERNANCE AND IMPACT REPORT IS EVEN MORE VITAL

For over a decade New Rules for Global Finance (New Rules) has engaged in reform of the institutions shaping global finance. We persist in asking: Who wins? Who loses? And, who decides? We continue to champion reform of the governance of these institutions, working to bring the voices of the excluded and affected peoples into the decision-making rooms; or as a poor second best, at least indirectly by getting their concerns and their wisdom inside the room. Those not among the deciders are likely to be the losers.

This second edition of the Global Financial Governance & Impact Report continues the immodest task of assessing the governance and impact of the institutions that write the rules for global finance: the Financial Stability Board (FSB); Group of Twenty (G20); International Monetary Fund (IMF); World Bank; and international tax rules-making bodies, focusing this year on the OECD.

Some might ask why this is important given that the world economy has largely emerged from the global financial crisis of 2008. The answer is that high-quality governance of global finance, ensuring that it has a positive impact on reducing global poverty and inequality, is even more vital if we are to accelerate global growth (which will be more sustainable if poverty and inequality are reduced), and avoid future crises which would throw such progress off course.

HOW WE HAVE ASSESSED GOVERNANCE AND IMPACT

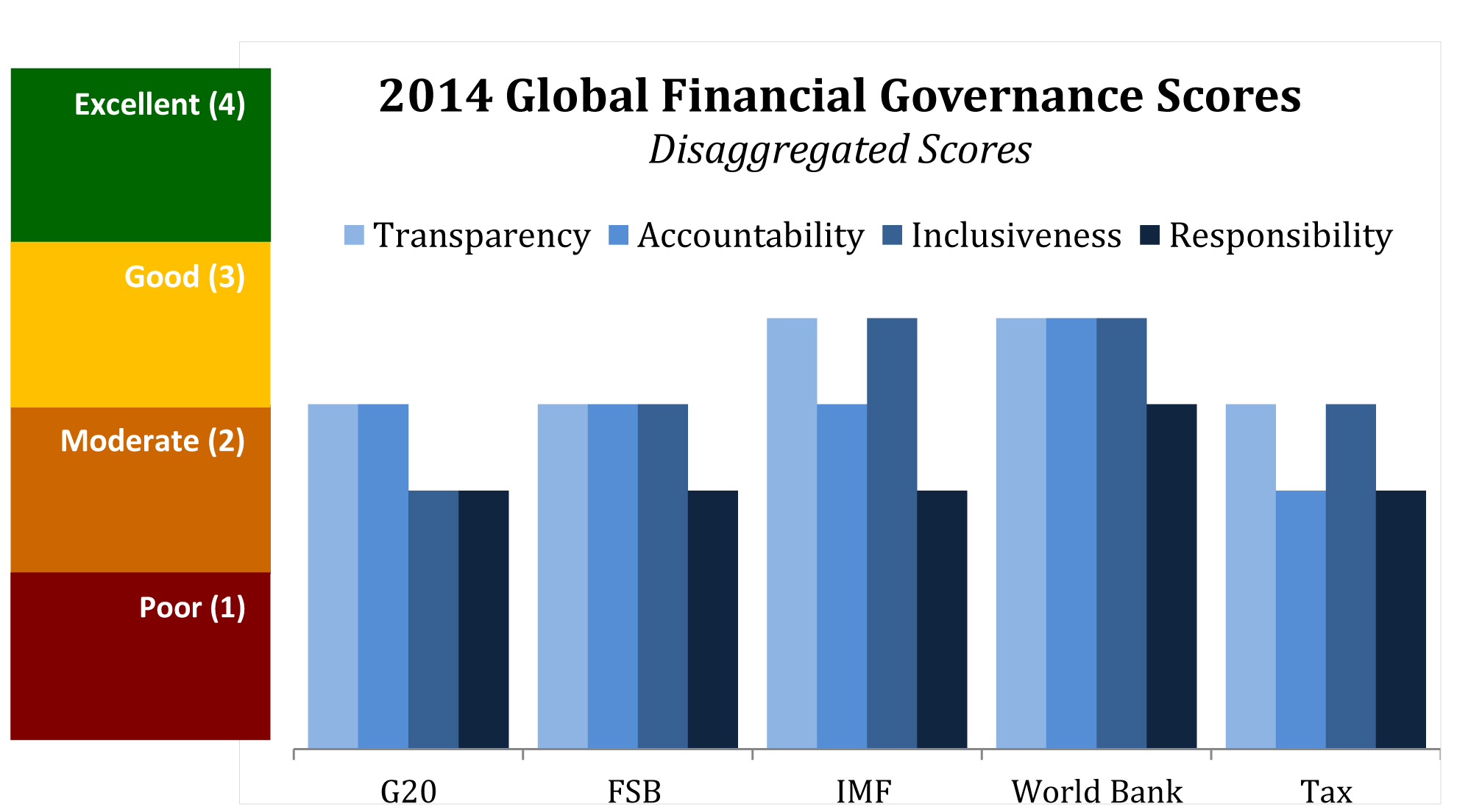

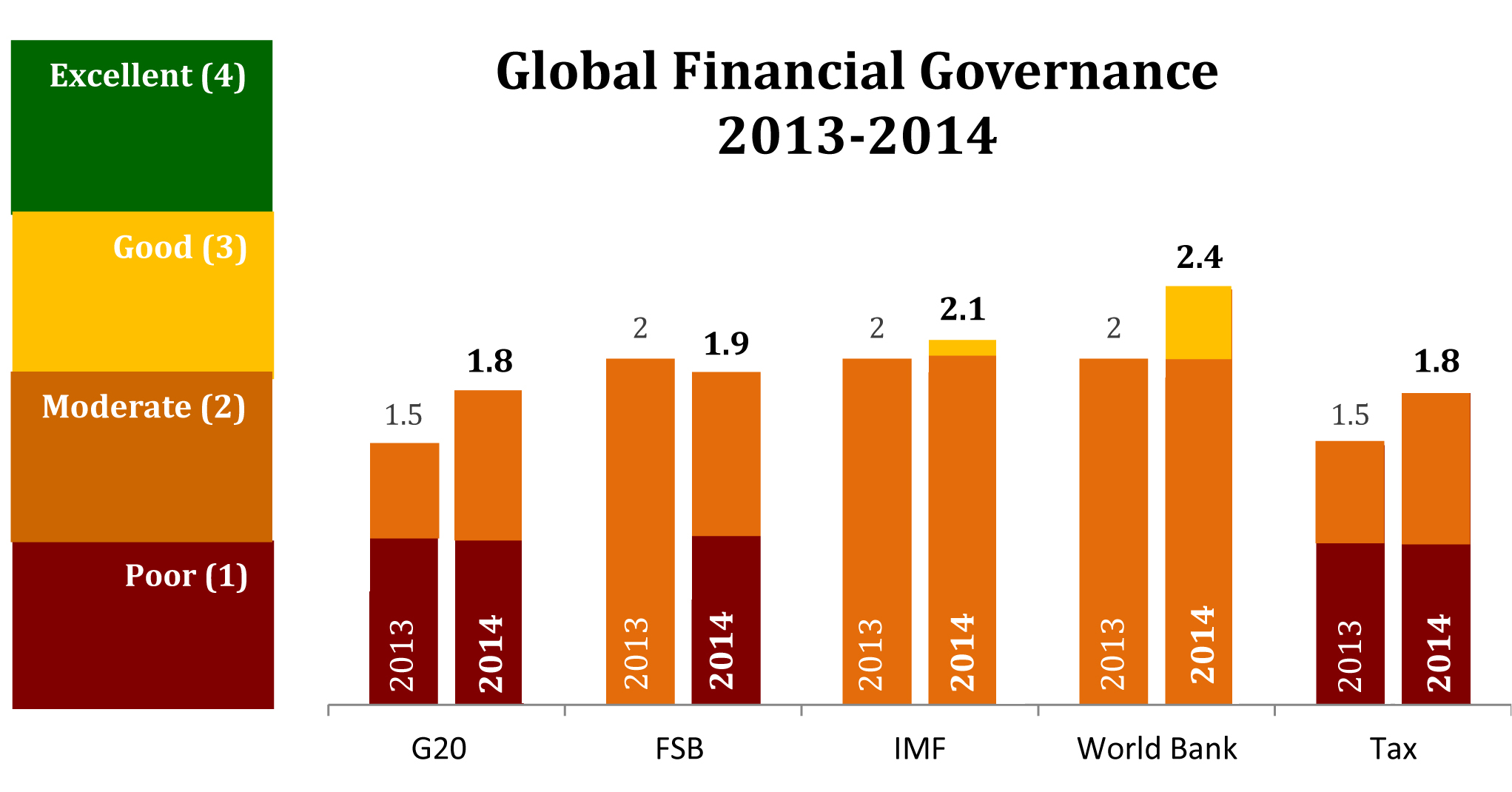

Our method for assessing the quality of global financial GOVERNANCE has not changed from last year – though information available to support the assessments has improved due to close cooperation with the institutions themselves and additional groups of independent analysts. The basic criteria remain the same:

Transparency: Any institution making rules that affect the entire world, must be held to the highest standards of transparency, so that those who make the rules will know the interests of and the potential impacts upon those excluded from the room; while those who are rule-takers can have maximum knowledge of how rules are made, whose interests are promoted, and whose rights protected. Each institution needs to make all documentation and data publicly available at the earliest possible stage, as well as providing all information necessary to explain their functioning and put stakeholders in touch with their representatives. For international tax rule-makers, we also consider the transparency of the policies the institutions promote: the current “system” favors secrecy so that the privileged or deceitful can hide and not pay their fair share for the common good.

Accountability: Each rule-setting organization must be fully accountable to member and non-member governments and to citizens and civil society, in line with its mandate, constitution and internal rules, as well as objective best practices for governance and management. All segments of the institution need to exercise responsibly the authority granted to them as limited by their charters, and not to exceed it through the exercise of raw power. This requires designing, monitoring and implementing measurable accountability frameworks; having open and merit-based selection processes for leaders and senior management; and regularly reviewing the functioning and achievements of their governance structures and meetings in holding management to account.

Inclusiveness: By rights all who are impacted by rules should have a voice in how they are made, evaluated, and amended. However, in a world of billions of citizens, we must accept representative democracy. New Rules supports constituency models which make governance inclusive yet small enough to get work done. The key to an equitable constituency model is a sound, objective basis on which voice and votes are allocated. The powerful will always be represented; but the real challenge is how well each institution ensures the presence and voice of the less powerful and those in need. The representation of non-state or non-governmental interests is also vital: again, while the “for profit sector” will have resources to make its views known, the key concern should be how well each institution listens to the poor and their representatives, and the silent imperatives of the global commons.

Responsibility: The external counterpart to Accountability is Responsibility. Each institution needs to ensure that its actions result in a stronger financial system that promotes more just and economically sustainable global development, especially for people in low income countries, without harm to the global commons. Responsibility requires that institutions assess ex ante for themselves whether their actions and recommendations are sure to have this positive impact; conducting independent ex post evaluations and impact assessments; and operating formal and independent complaint and anti-corruption mechanisms, with protections for complainants, and compensation for those harmed by any institutional action or inaction. It also requires that each institution learn from these assessments and change its behavior.

These four criteria are essential for good governance of any institution, especially when its actions and inactions significantly impact every country. Each governance section of this report analyses governance performance in detail, and uses a “Governance Scorecard” (available at the end of this report) to provide a summary assessment scale for each criterion, from “Poor” (1) to “Excellent” (4).

STRENGTHENING OUR ASSESSMENT OF IMPACT

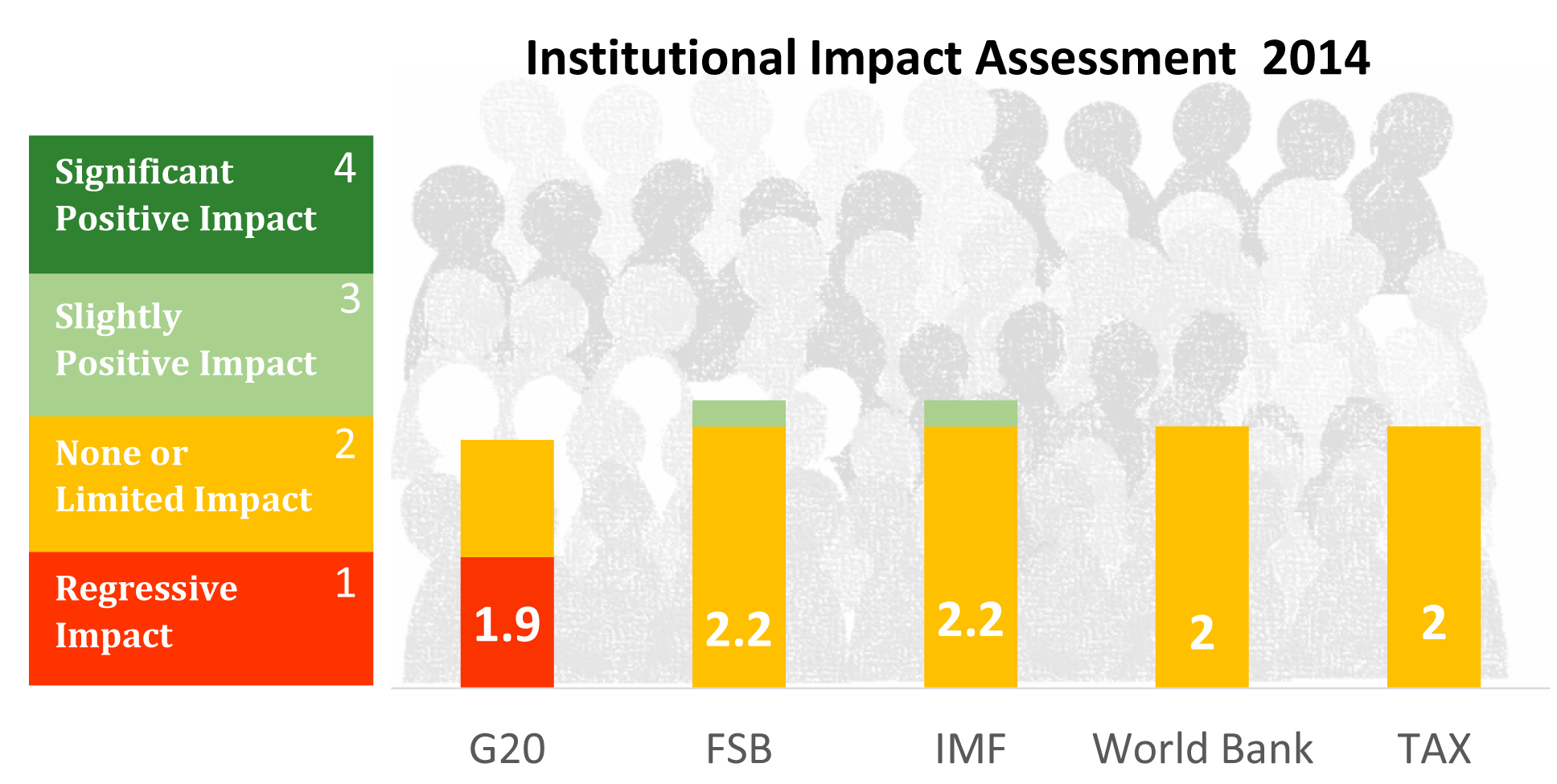

The center of attention this year has been on improving our methodology for assessing IMPACT. We have worked closely with a wide range of independent analysts and staff from the institutions themselves, who reached a consensus that the key criteria should be how these institutions affect poverty and inequality, based on the prominence of these issues in the post-2015 development framework and their prominence in all discussions (inclusive development is the theme of the Bretton Woods Institutions (BWI) Annual Meetings at which this report is launched). Global finance has a huge impact on the lives of the poorest people, and through them on the sustainability of growth as the institutions themselves have increasingly realized.

This becomes evident from examining the mandates of the institutions and their most recent statements of purpose. For each it has been relatively easy to identify five clear ways in which they should be combating poverty and inequality, though sometimes less easy to identify what they did to accomplish those objectives.

The G20 heads of state have defined their task as to ensure “balanced, sustained, and inclusive growth”. To achieve this goal, the identified priorities of the G20 should be:

- To address Global Tax Reform beginning with base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS), automatic exchange of information and public identification of beneficial owners of wealth;

- To shift its focus toward Inclusive Growth, addressing inequality globally and within G20 countries;

- To refocus its Development Working Group agenda around combating poverty and inequality, to make it more consistent with the post-2015 development framework;

- To promote Decent Work/Labor Rights and higher wages, and minimum social protection floors; and

- To mobilize long-term (especially concessional and official) development financing, including traditional official development assistance (ODA) and South-South cooperation, innovative financing, and reducing the costs of remittances.

The Financial Stability Board is mandated by the G20 to promote and ensure global financial stability – as the Deputy Secretary General has said “for what stability achieves” in terms of promoting sustainable growth. Its priorities to achieve this goal were:

- To end Too Big to Fail financial and insurance institutions;

- To design and implement cross-border financial resolution regulations (to resolve bankruptcies);

- To make transparent and regulate over-the-counter derivatives;

- To bring shadow banking into the sunlight of transparency, regulation and stability; and

- To organize the new Global Legal Entity Identification System (GLEIS) so every financial entity is identified and every financial transaction carries the “names and phone numbers” of all participants.

The International Monetary Fund works to ensure sustainable growth and the Managing Director has defined combating inequality as a core part of their mandate. It should be achieving these ends by promoting:

- Inclusive growth and decent and well-remunerated employment;

- More progressive taxes and more efficient tax collection, and combating tax evasion/avoidance;

- Anti-inequality spending, especially on education, health, social protection and water, sanitation and hygiene{Anchor:_GoBack} (WASH);

- Domestic and international financial systems that promote greater equality; and

- Lending adequate (low-conditionality) funds to countries to overcome balance of payments problems.

The World Bank has rearticulated its mission as ridding the world of extreme poverty and promoting greater inclusion for the bottom 40 per cent by 2030. It should be achieving this by:

- Defining strong targets for dramatically reducing inequality;

- Redefining its policy assessment and policy-based lending to ensure they fight poverty and inequality; supporting universal free education and health services, and social protection floors;

- Supporting the private sector in ways which reduce poverty and combat inequality;

- Providing large amounts of loans and grants to countries requiring long-term development finance; and

- The development of an overall framework to measure it own impact.

The OECD has long coordinated and advised on its member-states’ cross border tax policies. In 2013, the G8 and G20 expanded its mission to reduce the loss of income to all governments from tax avoidance and evasion through “Base Erosion and Profit Shifting”. We review the OECD’s achievements in:

- Monitoring, measuring and reducing illicit financial flows and tax evasion;

- Reducing major forms of tax avoidance;

- Ending “tax wars” or “tax competition,” which results in a race to the bottom for national revenue;

- Encouraging more efficient national tax administrations; and

- Promoting progressivity in national tax systems.

Authors assessed each of these functions in terms of their success in reducing poverty and inequality. The four point scale rated: 1-increased inequality; 2-no movement or inability to measure progress; 3- some positive movement; and 4-excellent progress. The total points were then averaged for a score for each institution.

A broad framework was designed to guide assessment of impact (see end of report).

The authors and the editors acknowledge that, in spite of improvements, the methodology used in this Report is still imperfect. It relies on publicly available data, and much more could be done to increase what is publicly available. A diverse panel of experts contributed most generously to thinking about results and methodologies. We incorporated this advice into our assessment and our overall findings are below. New Rules once again welcomes all feedback, especially whatever will improve the data sources and the methodologies used to assess both the Governance and the Impact of these institutions. As public bodies designed to promote the public good of a financial system at the service of reduced inequality and poverty in low income countries—with staff and facilities paid for by public taxes—we welcome the collaboration of the staff, management and leadership of the institutions, as well as that of the informed, articulate, and even boisterous public.