Global Financial Governance & Impact Report 2013: G20

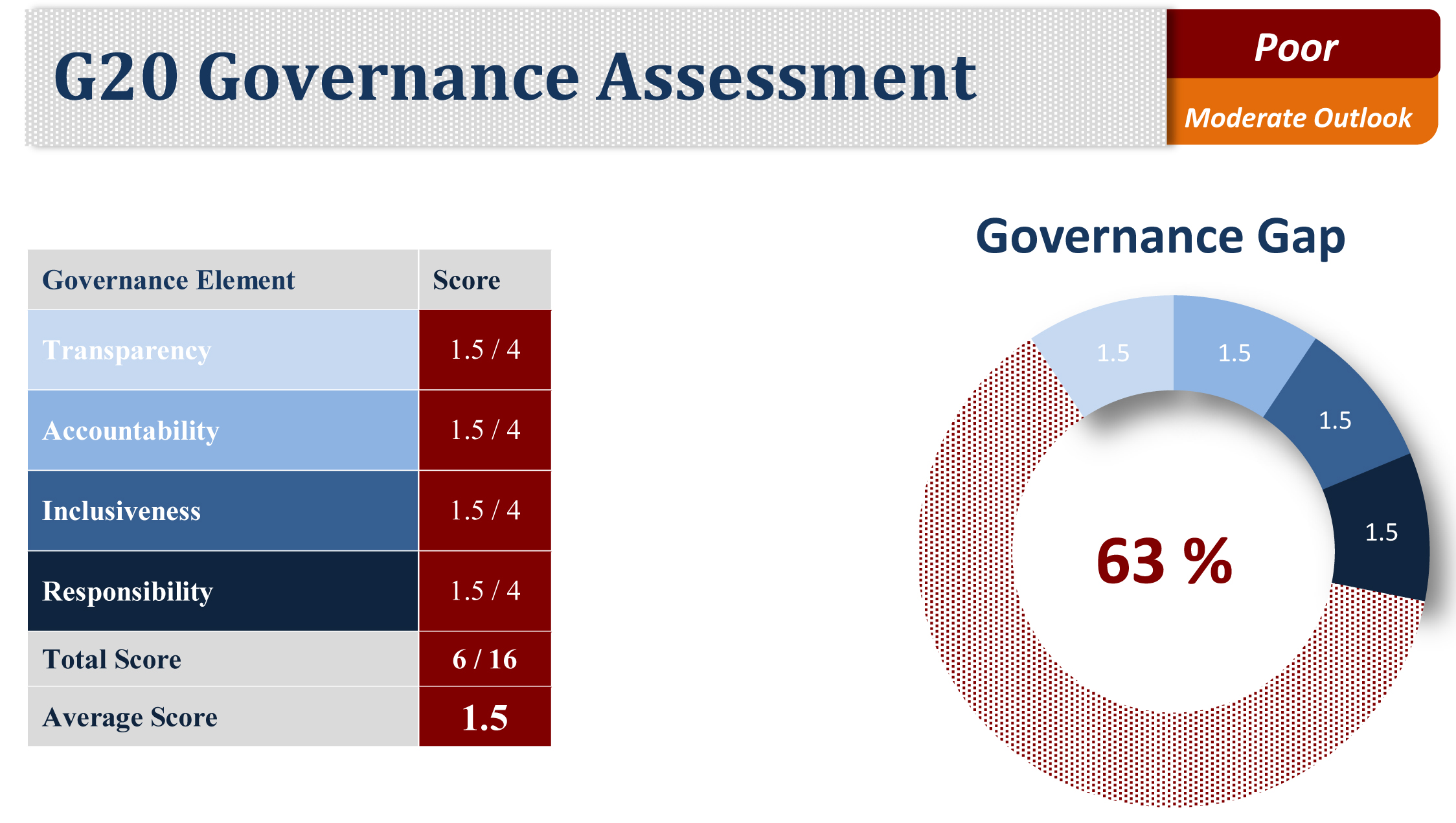

G20 Governance

Author: Nancy Alexander, Heinrich Boell Foundation

Introduction

As “the premier forum for international cooperation”, the Group of 20 (G20) is comprised of the 19 most economically powerful nations, plus the European Union (EU). The G20 member countries represent 90% of global GDP, 80% of international global-trade, two-thirds of the world’s population, and 84% of all fossil fuel emissions.

This section presents information and perspectives about governance of the G20 – specifically its track record in terms of inclusiveness, transparency, accountability and responsibility. Although these are desirable values, particularly for a relatively new global governance body, the G20’s capacity to excel in these areas is limited by its nature.

Specifically, the G20’s accountability is limited by the fact that:

- Member countries were not selected according to objective criteria. Rather, they were selected based on the subjective judgment of the U.S. and Canadian Finance Ministers in the aftermath of the East Asian Financial Crisis. The member countries were chosen to represent their own interests – not the interests of their region, although some regional consultative practices have emerged over the years. In other words, from the outset, the G20 was not intended to be an inclusive or representative body.

- The G20 is an informal entity that lacks any charter or articles of agreement setting forth its purpose and designating where its powers begin and end. Moreover, it is not accountable to any other, more representative body, such as the United Nations. Therefore, the G20 can only be held accountable to its own policy frameworks, such as:

- The Framework for Strong, Sustainable and Balanced Growth, which sets out the economic goals and objectives for G20 member countries, themselves, together with some collective goals;

- Development Action Plans (DAPs), which sets out the goals and objectives of the G20 countries, particularly relative to low-income countries; and

- The Anti-Corruption Working Group’s Action Plan.

Meanwhile, the G20’s power is expanded by:

- Its dominance in international organizations. The G20 countries make up the membership of the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and often hold sway in international organizations. Indeed, its member countries hold the vast majority of votes in the international financial institutions (IFIs). As a result, the G20 – as a non-representative body – can direct the workings of the IFIs – which are imperfect, but still representative, institutions.

- The G20 as a Network. The global financial architecture is altered, not only by the existence of the G20, but also by the multiplicity of G20 collaborations, which creates the effect of a global “cabinet”. For instance, in addition to its Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Meetings, the G20 has convened its Labor, Agriculture, Energy, Tourism, and Foreign Ministers.

The G20 also networks through initiatives, such as its “Financing for Investment” initiative to mobilize long-term infrastructure finance. In this effort, the G20 collaborates with the World Economic Forum and regional bodies and initiatives, such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Infrastructure Fund; the Program for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA); and the Initiative for the Integration of the Regional Infrastructure of South America (IIRSA). This effort also involves an exploration of how to change the mandates of national and international development banks to promote public-private partnerships (PPPs), particularly in infrastructure.

Inclusiveness

The G20 membership includes 19 countries and one region:

- The G8: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, U.K., U.S.;

- The “Rising 9”: Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, South Africa, South Korea, and Turkey;

- Australia and Saudi Arabia; and

- The European Union.

In an attempt to address the fact that its membership excludes 173 countries, the G20 invites the participation of non-member countries at the Leaders’ Summit and Sherpa, Ministerial and Working Group discussions. In addition to Spain, which is a permanent observer, the G20 President invites four non-member countries taking into account geographical representation and including countries which preside over regional fora (African Union [AU], NEPAD, APEC, ASEAN) and the Global Governance Group (3G), which is described below).

To its Summit, the Russians invited Ethiopia (Chair, AU), Senegal (Chair, NEPAD), Kazakhstan (Commonwealth of Independent States), Brunei Darussalam (Chair, ASEAN) and Singapore (Chair, 3G). In addition, representatives of international organizations attend: the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the World Trade Organization, the Financial Stability Board, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the United Nations, and the International Labor Organization (ILO).

Non-State Actors. The President of the G20 determines the type of relations the body maintains with non-state actors, including business, labor, civil society, youth, young entrepreneurs, and women. During the U.S. G20 Presidency, there were few interactions between the G20 and such groups. The Canadian G20 Presidency was not much better. The level of ambition is increasing with regard to the Russian outreach strategyand early indications of the Australian strategy.

In general, G20 relations with Think Tanks and Civil Society are not as regular and transparent as they are with the Business 20 (B20). The Civil 20 met with Sherpas during the South Korean Presidency. Meetings with G20 officials were more regular under the Russian Presidency, although many actors considered this a charade. That is, while it engaged in extensive repression of domestic civil society activities, the Russian government used Civil 20 consultations to polish its image. During the Australian Presidency, Think Tanks – led by Australia’s Lowy Institute – promise to play the strongest role in any summit process to date.

Transparency

Three types of transparency are important:

(1) Disclosure of information by the G20 Presidency. In recent years, when the Presidency of the G20 has rotated, the website of the outgoing G20 President disappears and the incoming G20 President usually constructs a new website. In an era when so much research and communication occurs via the internet, this practice is disruptive. The G20 website should be a permanent fixture, but maintained by the G20 Presidency with assistance from its Troika partners.

Regarding Summits, Ministerial groups (i.e., Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors), and its working and expert groups, the G20 Presidency should disclose the lists of members, meeting agendas, background papers, commissioned papers, and minutes of meetings in a timely and proactive manner for public access. This does not currently occur. The G20 does not disclose the membership list for its sub-groups or meeting agendas. It discloses often-cursory summaries subsequent to some meetings, which may or may not contain the decisions made. Commissioned papers are not routinely published on the website of the G20 or the organization (e.g., the World Bank, the OECD, etc.) that prepares the papers.

(2) Disclosure of G20 Commitments. There is a great deal of opacity about the inner functioning of the G20 Ministerial groups and working groups (e.g., Framework Working Group; Anti-Corruption Working Group; Energy Sustainability Working Group, International Financial Architecture Working Group; Financing for Investment Study Group; Climate Finance Study Group). However, there are vehicles by which the G20 discloses its commitments, such as:

- In 2009, the G20 set up a “Framework for Strong, Sustainable and Balanced Growth,” which is a multilateral process through which the G20 identifies objectives for the global economy and the policies that member countries need to implement to achieve the objectives. The policy commitments by G20 Members are appended to each G20 Summit Declaration.

- In 2010, the G20 launched a three-year Development Action Plan (DAP), which set forth the nine objectives for G20 relations with non-member countries, particularly low-income countries.

- The Anti-Corruption Working Group sets out its commitments in Action Plans.

(3) Disclosure by each G20 member country, the EU, as a region, and routine observers (Spain, ASEAN, AU, NEPAD, 3G). Each participant should also maintain a website that provides a comprehensive view of its engagement in the Group, including points of contact for external stakeholders. Democratization of the G20 depends upon citizens and their elected officials having decisive input to G20 officials at the national level. Government contact points, or liaisons, should conduct regular meetings and exchanges so that citizens’ groups can not only make their positions known, but engage in decision-making processes, and learn about final decisions made.

It is also important that Major Groups disclose their activities and recommendations; this includes the Business 20 (B20), Civil 20, Think Tank 20, Youth 20, Young Entrepreneurs 20, and G(irls)20. However, when the G20 Presidency rotates annually, it is not always the case that civil society groups (which are, by definition, diverse) have the will and capacity to organize themselves and present a common front. While most civil society groups would prefer to self-select and organize a common front with international partners, the G20 Presidency in Russia and Australia has selected and/or funded domestic citizens’ groups to perform this function.

Accountability

Relations with Non-Member Countries: The G20 member countries should exercise “upward” accountability to the entire community of nations for the policy actions they undertake and “outward” accountability to groups of non-member countries and other stakeholders. In addition, it is important to assess the G20’s compliance with its commitments.

Upward Accountability: It would be ideal if a body, such as the G20, comprised a Global Economic Coordination Council, as recommended by a 2009 Report of a Commission of Experts on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System. Then, it would be accountable to the world community rather than it itself. Although such a proposal is a political non-starter, the G20 can and should strengthen its communications with the UN.

At the UN, a liaison group – the Global Governance Group (3G) – was created in 2010. Led by Singapore, the 3G is comprised of about 30 small- to medium-sized non-G20 member countries. It set out the process by which the G20 should be accountable to the community of nations: “Strengthening the Framework for G20 Engagement with Non-Members.” Speaking on behalf of the Global Governance Group at the United Nations in April 2013, Albert Chua stated:

“In the 3G’s view, the United Nations must continue to lead the effort in shaping the global governance framework. As the only global body with universal participation and unquestioned legitimacy, the United Nations has a central role in global governance.”

The International Financial Institutions (IFIs) – namely the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank – are nearly-universal forums. Yet, the G20 is not accountable to the IFIs; in some respects, these bodies are accountable to the G20. For instance, the G20 has mandated that the IFIs conduct analysis and research on its behalf. In some instances, the G20 acts like a caucus inside the IFIs – for instance, with regard to reform of the IMF governance and voting system.

Outward Accountability: Since regional bodies, such as the AU and ASEAN, are G20 observers, they could facilitate consultation in the run-up to a G20 Summit. Sometimes, the regional consultation mechanism may be formalized. For instance, the “Committee of 10” (C10) comprised of African Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors was created in 2008 to, among other things, identify strategic economic priorities for Africa and develop a clear strategy for Africa’s engagement with the G20. At its last meeting in Washington DC in April 2014, the C10 encouraged diversification to overcome economic vulnerability and call for strong support for the African Development Fund.

In addition, some types of consultations are becoming a tradition, such as the G20 engagement with the Commonwealth countries.

Compliance with Commitments: Compliance is measured by the G20 itself, through peer review; by international organizations; and by outside groups.

For the September 2013 G20 Summit, the G20 produced its Accountability Assessment (AA), describing its (non) compliance with the AA’s framework goals. Through a “Mutual Assessment Process” (MAP), the IMF works with G20 member countries to assess compliance with their framework commitments (e.g., financial, fiscal, monetary and exchange rate, structural policies) in the context of the “Framework for Strong, Sustainable and Balanced Growth” which contains the most important commitments made by the G20.

In the future, the G20 will utilize a peer review methodology to assess each other’s implementation of the commitment to remove fossil fuel subsidies. Its 2013 Progress Report assesses the Anti-Corruption Working Group’s performance.

It is commendable that the G20 has produced the St. Petersburg Accountability Report on G20 Development Commitments for the September 2013 Summit, but many observers would question its conclusion that the implementation of only one commitment out of 67 has stalled. The St. Petersburg Development Outlook includes the development actions that the G20 intends to undertake in the next three year period. (See below)

In terms of non-state actors, the International Chamber of Commerce releases an annual “G20 Scorecard,” that ranks G20 performance according to the priorities of member country businesses. The G20-B20 Dialogue Efficiency Task Force Report found that, of the total of 262 business recommendations, 93 or (35.5%) have been reflected in the G20 documents as commitments or mandates. Civil society recommendations to the Russian G20 Presidency were developed with difficulty, in part because the Russians chose co-chairs from the business community for three of the seven working groups that developed these recommendations. Efforts by civil society to assess G20 accountability are ad hoc in nature.

The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) provides clear recommendations for policy discussions at G20 Leaders’ Summits as well as Summit evaluations. The G20 sometimes makes more progress on modest “asks,” such as those relating to youth apprenticeships than to weightier “asks,” such as to “Take targeted action to support aggregate demand and employment in those countries facing a serious slowdown in growth or slipping into recession; and put an immediate halt to austerity measures and corresponding cuts in public spending in areas that provide social support…”

The University of Toronto and the Higher School of Economics (Moscow) attempt to rank G20 performance objectively in seven areas: 1) implementation of structural reforms, 2) overcoming imbalances, 3) international financial institutions reform, 4) financial market regulation, 5) protectionism, 6) phase out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, and 7) development. Their 2012 report entitled, “Mapping G20 Decisions Implementation: How G20 is delivering on the decisions made” (the “Mapping… document) suffers from methodological problems in identifying actual commitments and instances when they are implemented. Yet, there are deeper problems:

- All commitments are not created equal. The methodology provides equal weight to performance with regard to commitments.

- Implementation of some development-related commitments could undermine the sovereign will of low-income countries that have not participated in the design of those commitments. For instance, West African countries rebuffed the G20’s attempts to pilot a regional food security reserve.

- Implementation of G20 commitments to cut minimum wages, job protections, and unemployment insurance can short-circuit domestic laws and bargaining rules.

- Implementation of some commitments can undermine other commitments. For instance, as the authors of the “Mapping…” document recognize, there are trade-offs between fiscal consolidation and creating jobs and growth. Commitment to trade liberalization can conflict with its commitment to job creation; commitment to infrastructure could potentially undermine its commitment to “green growth;” and commitments to business climate reform can conflict with its commitment to create quality jobs and financial stability.

Responsibility

While it is beyond the scope of this article to provide an agenda to improve the G20’s effectiveness, measures in three areas are proposed:

Austerity vs. Growth and Jobs: The ultimate test of G20 effectiveness is its contribution to economic recovery and sustainable development. In 2008, when the G20 began meeting at the ‘heads of state’ level, it resolved to promote global economy recovery and rebalancing. In 2008-2009, the G20’s global stimulus program helped avert depression, yet in 2010-2013, the G20 prematurely promoted too much fiscal contraction in too many places. Expansionary monetary policy by the U.S. and other advanced economies may have reached its limits, yet the world economy remains precarious.

Financial Institutions and Flows: Today, financial power is more centralized in bigger and fewer financial institutions than at the time the global financial crisis erupted. The “shadow economy” remains largely unregulated with little progress toward achieving greater transparency of the over-the-counter (OTC) market in derivatives – a market that is so large and opaque that it destabilized the world economy. To safeguard the future of the global economy, the G20 should both strengthen and implement its roadmap on oversight and regulation of shadow banking, which was adopted at the St. Petersburg Summit. Arguably the most impressive outcome of this Summit was the G20’s call to rein in illicit financial flows by, among other things, ensuring that policies relating to automatic disclosure of (tax) information are implemented. Without such steps, corporations will enjoy “double non-taxation” and governments will be deprived of the revenues needed for development.

Development: At the 2010 South Korea G20 Summit, a Development Action Plan was launched with nine pillars: infrastructure, food security, financial inclusion, human resource development, trade, private investment and job creation, growth with resilience, domestic resource mobilization and knowledge sharing. In practice, the primary focus has been on the first three pillars, but the results are not highly consequential. Indeed, one former member of the G20 Development Working Group calls the DAP invertebrate, flabby, and toothless.

During the next three years, 2014-2016, the G20 will implement five development priorities relating to food security, financial inclusion and remittances, infrastructure, domestic resource mobilization and human resource development. While the G20 will continue its own performance with regard to commitments in these areas, more non-state actors should provide independent assessments.

The G20 should ensure that the entire gamut of its policies have positive consequences for poor people and low income. This requires using UN channels to engage the 173 countries excluded from G20 membership, especially low income countries, in re-shaping the agenda to suit their purposes. It also entails tackling inequality, including gender inequality, and climate change as key cross-cutting issues.

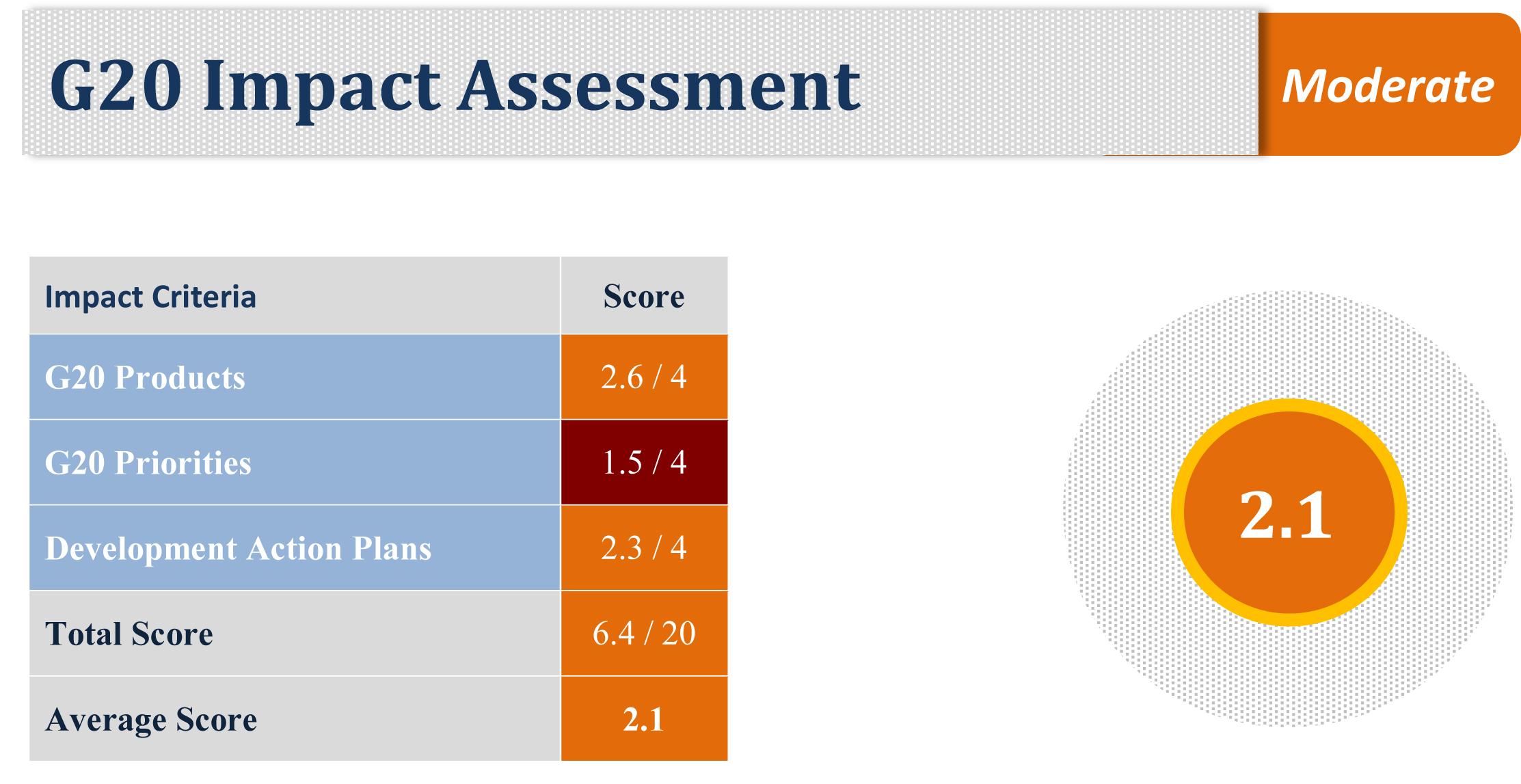

G20 Impact

Author: Nathan Coplin, New Rules for Global Finance

Actions taken by the G20 – which represents more than 90 percent of global GDP and 80 percent of global trade – have significant implications for non-G20 countries, especially developing countrieswhich are more vulnerable to external factors and oscillations in the global economy. Despite this impact, most developing countries are excluded from the G20 decision-making process, making it all more important to assess the impact of G20 actions on such countries.

Currently, there is no solid framework for assessing G20 impact. Most evaluations of the G20 process focus primarily on compliance with commitments [see G20 Governance Chapter]. A 2012 report admits that its review of compliance “does not attempt to estimate the impact or effectiveness of the G20 actions.” Some observers have labeled the G20 process, particularly in its development efforts, a failure or suggested that the G20 should not even be involved in the development agenda. Nevertheless, given the collective economic influence of the G20, their actions will have an impact – positive or negative – on developing countries.

Although a comprehensive assessment is beyond the scope of this chapter, the goal of this evaluation is to develop a preliminary assessment of G20 impact. First, it is difficult to link G20 actions and impact, particularly because its actions are actually implemented by member countries, the private sector and international institutions. To account for the various linkages between G20 actions and their impacts in developing countries, this evaluation considers three approaches: 1) identifying the actual “products” attributable to the G20 and their observable outcomes [i.e. what it has done]; 2) evaluating G20 priorities [i.e. what it is doing]; and 3) evaluating G20’s Development Action Plan (DAP) [i.e. what it has commuted to do].

Products of the G20

This section evaluates the “products” of the G20, defined as: tangible and recognizable actions attributable to the G20. An example of a G20 product is the coordinated fiscal stimulus package in 2009.

Coordinated Stimulus Package: Arguably the greatest achievement of the G20 to date is its coordinated stimulus package at the 2009 London Summit. The G20 mobilized id=”mce_marker”.1 trillion to withstand the global financial crisis, with $50 billion directly allocated towards low-income countries through multilateral development banks (MDBs). This fiscal injection helped suppress an impending global economic depression – and was instrumental in safeguarding the economies of many developing countries, especially small export-driven economies dependent on external demand. However, the stimulus was insufficient to alleviate the suffering from the subsequent food crisis. The continuation of weak economic growth, high rates of unemployment and income inequality means the suffering continues, especially in LICs. Nevertheless, the G20 coordinated stimulus is largely viewed as preventing this damage from being much worse. [Slightly Positive: 3]

Establishment of the Financial Stability Board (FSB): The expansion and institutionalization of the FSB has strengthened to the development and promotion of reforms in the global financial system, such as the Basel III Accords. To date, the implementation of these reforms has been insufficient. However, the formalizing of the FSB institutional framework improves the outlook for regulatory cooperation and early identification of systemic vulnerabilities. Enhanced coordination on regulations for issues such in OTC derivatives, shadow banking and Systemically Important Financial Institutions (SIFIs) should improve the resilience against future financial crises and mitigate the costs developing economies suffer in their aftermath. [Slightly Positive: 3]

Remittance Transaction Costs: In 2011, the G20 committed to lowering the transfer costs of remittances by 5 percent globally. Since then, the G20 has launched the G20 Remittance Toolkit, increased funding to the World Bank Remittances Trust Fund and the AfDB Migration and Development Initiative which support capacity building of local remittance operations. These efforts resulted in an additional USD 1 billion going to poor families in developing countries each year. Despite this progress, reductions in global average remittance costs have been meager. According to a 2013 World Bank report, average remittance costs have only declined to 8.85 percent from 10 percent in 2011. Any decrease has a positive impact, but at this rate, remittance costs will not reach 5 percent until 2020 – meaning that recipient families will essentially forfeit an estimated USD 19 billion. [Neutral: 2.5]

Delegating and Mandating to International Institutions: The G20 facilitated implementation of the 2008 IMF Reforms and 2010 World Bank Reforms, which improved the representation of emerging market and developing economies in the IMF and World Bank. The G20 was also instrumental in tripling IMF resources in 2009 to $750 billion, which proved beneficial for developing countries facing balance of payment problems in the aftermath of the financial crisis. Further increases in resources followed the Los Cabos commitments. However, the G20 has failed to deliver on the 2010 IMF governance reforms. This means the IMF has more resources at its disposal, but the decisions for using these resources will be made by an Executive Board where developing countries are underrepresented. Furthermore, there is concern that the additional IMF resources (which includes funds from developing countries) will be used to bailout EU countries facing debt crises. Greece and Cyprus have already received close to US $40 billion from the IMF.[Slightly Negative: 2]

A major impact of G20 delegating tasks to the IFIs is that it undermines the voice and power of developing countries in these institutions (see G20 Governance chapter). Undermining these governance arrangements erodes the ability of developing countries to influence decisions (that will most likely impact them the greatest).

Other Products: The G20 launched a pilot project for regional emergency food reserves in West Africa in 2011. However, the pilot project failed as it was actually rejected by West African countries. Since most developing countries are excluded from the G20, its efforts in these countries will often risk failure. Nevertheless, there are a number of other G20 efforts that could emerge as “G20 products”, such as the AgResults Initiative Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS) or MDBS Infrastructure Action Plan (MIAP).

G20 Priorities: Consistent and Meaningful Actions

Unlike the “G20 products” above, G20 priorities do not necessarily result in tangible and observable actions. Therefore, it is even more difficult to draw correlations between G20 priorities and their impact in developing countries. The rhetorical priority of the G20 is “Strong, Sustainable and Balanced Growth”. Despite this commitment, income inequality has risen in nearly every G20 country since 1990. According to its own 2013 St. Petersburg Report, the G20 admitted that growth is not strong, not balanced, and has slowed down in emerging markets; and market volatility has increased. The G20 has failed to deliver on this commitment.

It is important to understand what led to this failure. At each Leaders’ Summit, the G20 makes a plethora of commitments. The 2013 St. Petersburg Summit alone produced 113 commitments. Many of these commitments are formalities, political rhetoric or inconsequential pledges; however, some lead to meaningful and consistent G20 efforts. Given the G20’s collective economic power, where the G20 decides to concentrate its efforts matters greatly. These efforts reveal the genuine priorities of the G20 and can help explain this failure and the real impacts of the G20.

Determining G20 Priorities: For this evaluation, a policy area is a G20 priority if it meets the following two criteria: commitment to policy area is consistent (committed to in 4 of 6 last Summits); and commitments are implemented (highest rates of compliance in 4 of 6 last Summits). Table 1 shows the policy areas with the highest levels of implementation for each Summit, of which only two can be considered G20 priorities: Reducing Protectionism; and Macro Policy. The G20 has continually pursued action (or finds it easier to act) in these policy areas. An assessment of these policy positions impact developing countries follows:

Reducing Protectionism: Despite evidence that there is no systematic relationship between tariff or non-tariff restrictions and economic growth,the G20 has made it a priority to reduce or eliminate these restrictions. However, G20 countries have rarely adjusted their own trade barriers. This G20 priority, instead, manifests itself in trade agreements and in the rules promulgated through international institutions such as the World Trade Organization. This has considerable negative implications for the negotiating positions of developing countries in international trade agreements, particularly for countries trying to protect infant industries or the stability of their financial system.[Negative: 1]

Macro Policy: The G20 Research Group reports, the 2013 G20 Mutual Assessment Process (MAP) report and the 2013 St. Petersburg Accountability Assessment affirm that Fiscal Balance is the G20’s greatest priority. The coordinated stimulus was a net plus for advanced and developing economies alike, but the recent emphasis on fiscal consolidation has had (and will continue to have) significant consequences for developing countries in two ways. 1) Policies in G20 countries: Fiscal consolidation in advanced economies slows growth and reduces global demand for developing country exports. It is worth noting that a 2013 survey by the Center for International Governance Innovation (CIGI) finds that Macro Policy cooperation has actually regressed. This means that the negative effects of concentrated fiscal consolidation may be less likely, but it also means that future coordination for fiscal stimulus packages may be less feasible as well. 2) Policies in International Institutions: Like other G20 priorities, the emphasis on fiscal consolidation manifests itself in international institutions, particularly IFIs, through their policy advice and loan conditions. As a result, fiscal austerity has become practice in developing countries and led to direct impacts for the real economy: reduced job creation, reduced spending on education, public health, infrastructure, etc. A 2013 South Centre report – based on IMF data – found that government spending in developing countries contracted nearly triple the rate of high-income countries from 2010-2012. The report projects that 68 developing countries will contract even further during the 2013-2016 period.

[Slightly Negative: 2]

According to the most recent G20 Research Group report, compliance has been highest for Fiscal Consolidation, IFI Reforms, and Development commitments. It is discouraging to see that fiscal consolidation remains a key priority for the G20 and the G20 has struggled to implement significant IFIs reforms. Development has become a greater focus since the 2010 Seoul Summit, but the results of these efforts have been unclear and even counterproductive.

Development Action Plans

While the G20’s Development Action Plans (DAPs) should provide the best insight into the impact of G20 actions on developing countries, they have been little impact to date. In an August 2013 article Steve Price-Thomas and Sabina Curatolo find that so far the “G20’s actions have failed to match its ambitions.”Nevertheless, the G20 has claimed that it can deliver “tangible development outcomes.” The 2010 Seoul Multi-Year Action Plan (MYAP) on Development outlined 9 areas or “pillars” where the G20 believes it can deliver these outcomes. Among these 9 pillars, commitments have been concentrated in three: infrastructure, food security and financial inclusion, the focus of this section.

Infrastructure: The key achievement under this pillar has been the High-Level Panel for Infrastructure Investment (HLP), which has unlocked some binding constraints for infrastructure finance and improved strategies for project preparation. Given the enormous need for infrastructure in developing economies, this could have a significant positive impact. Since the majority of financing will be facilitated by MDBs, the main concern is whether MDBs have adequate safeguards for the economic, social and environmental impacts. In 2011, the HLP and MDBs agreed on criteria for selecting infrastructure projects to finance. One of the criteria was that projects must have “high development impact on a large number of people and promote environmental and social sustainability.” This is commendable, but must be put into practice to achieve its intended positive impacts. According to its own 2013 report, the G20 has failed to do this. This report found that the G20’s commitment to “assess how to integrate environmental safeguards into its MIAP” has completely “stalled” (Among the G20’s 67 development commitments, this is the only one with this status). Furthermore, safeguards for social sustainability are not even considered in the G20 MIAP.

Further analysis of the G20 ARD brings into question the accuracy and legitimacy of the report itself. For example, the commitment to ensure that the MIAP has “a sharper focus on environmental sustainability” is considered to be “complete”. This is puzzling since the same report finds that “No specific recommendations appear to address this [environmental sustainability] in the MIAP or the HLP report.” The G20 is overlooking the social and environmental impacts of infrastructure projects, yet its 11 selected projects continue to move forward. [Slightly Negative: 2]

Food Security: There have been three major food price hikes in the last five years. Given the need for greater stability in global food prices, the G20 has made this a priority in its MYAP, which is commendable. Regarding the G20’s commitments, there has been some moderate progress – such as the development of the AgResults Initiative, Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS), Rapid Response Forum (RRF), the Platform for Agricultural Risk Management (PARM) and other initiatives. The AMIS initiative, which aims to increase transparency in agricultural markets, reported that the supply situation for AMIS crops (wheat, maize, rice, soybeans) improved but is difficult to attribute causality the AMIS initiative. The AgResults initiative has USD 100 million in pledged funds and established a secretariat, but its three pilot projects for Kenya, Nigeria and Zambia have yet to launch. The impact of AMIS and AgResults is difficult to determine at this time, but the outcomes of these initiatives may help reveal the micro-level impacts of G20 actions and warrant close monitoring (AgResults promised to track its outcomes with an “external impact evaluator”). A key concern is that these initiatives are established without input from developing countries, which threatens their success and may contribute to the failure of the pilot project in West Africa.

The area where the G20 has the most potential to improve food price stability – mitigating excessive speculation in commodity markets – has been disregarded. Instead the G20 has focused on mitigating risks associated with price volatility. This is also important, but impactful programs requires participation and cooperation from developing countries (as noted earlier, this is not how the G20 process works). Since financial markets and regulatory authorities are concentrated in G20 countries, implementation of new rules to curb excessive speculation should be more feasible. The G20 should mandate an FSB review of relevant regulation in commodity markets. [Slightly Negative: 2]

Another area where the G20 has a similar comparative advantage is on Domestic Resource Mobilization (Pillar 8). If the G20 does not take adequate and meaningful action to address tax evasion and avoidance, it should be considered an enormous failure for both global economic cooperation and development.

Financial Inclusion: The major achievement under this pillar is the establishment of the Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion (GPFI) in 2010. Brazil and Nigeria have both launched national strategies for financial inclusion; and according to the G20 ARD, Chile, Tanzania, Mexico, and Rwanda are preparing theirs. This could be partly attributed to the G20’s efforts on this issue. In addition, the G20 launched the SME Finance Challenge in 2010 to stimulate innovate models for financing SMEs. So far, 13 winners have received grants – US $23 million in total – and as of December 2012, the grantees had assisted over 1000 SMEs in receiving loans. This initiative has proven somewhat effective, albeit on a small scale, and could lead to truly positive impacts for SME loan recipients. For the most part, the G20 is simply raising the profile of financial inclusion issues, not pushing particular actions or initiatives onto developing countries. This in itself may have a positive impact. [Slightly Positive: 3]

Overall Assessment: This evaluation outlined a framework for assessing G20 impact on developing countries by evaluation three areas of G20 action. It identified the G20’s key “products”: the 2009 Coordinated Stimulus Package, the FSB, Delegation to IFIs, and Remittance Cost Reductions. This evaluation finds that the overall impact of these products has been slightly positive. In regards to the G20’s priorities – Macro Policy and Reducing Protectionism – the overall impact and outlook is slightly negative. The G20’s efforts on development, particularly on infrastructure, food security and financial inclusion, have not had any meaningful and observable impact. However, some G20 actions on infrastructure and food security could lead to potential consequences for developing countries. There are some positive developments as well, such as enhanced engagement with non-G20 members; and acknowledgement by the G20 that is should consolidate its development efforts to a few key areas. The overall assessment is that G20 actions are having a neutral impact on developing economies, but with a negative outlook at this time.

The report can be accessed through the attached link: