Global Financial Governance & Impact Report 2013: IMF

IMF Governance

Author: Jo Marie Griesgraber, New Rules for Global Finance

Purpose: To inform the public and the persons and governments responsible for the actions of the IMF regarding New Rules’ assessment of the quality of IMF governance and of its actions, both to praise where it has performed well and to encourage improvement in the future where it has not performed well, using a metric similar to that which the Financial Stability Board (FSB) designed to publically evaluate its own work in its reports to the G20.

New Rules for Global Finance believes that finance needs to serve the real economy in a stable manner. Reforming the rules and institutions governing international finance and public finance can support just, inclusive and economically sustainable global development. New Rules will assess IMF governance by considering four core elements, with their corresponding purposes:

A. Transparency: To ensure that the deliberations, decisions and documentation of the IMF are fully transparent to all stakeholders, and that the policies they endorse promote transparent global and national financial policies and regulations.

B. Inclusion/Participation: To enable those affected by IMF actions to maximize their voice in the decisions the IMF makes, while promoting universal representation through a fair constituency mechanism.

C. Accountability: To strengthen the IMF’s adherence to its own highest standards, answering to member governments and through them to their citizens, by rewarding best policies and practices and rooting out inappropriate and even harmful institutional policies and practices.

D. Responsibility: To ensure that IMF actions result in financial governance and regulations which promote more equitable and economically sustainable global development, especially for the most vulnerable populations.

The IMF’s highest body, the Board of Governors, is comprised of one representative from each member-country who is either a Finance Minister or head of the Central Bank. The Board meets annually and in the time between meetings the International Monetary and Finance Committee advises the Executive Board through its biannual meetings. The Executive Board, comprised of 24 resident Executive Directors (ED), at the IMF headquarters in Washington, DC, conducts most of the business of the Fund meeting several times each week. It carries out its work largely on the basis of papers prepared by IMF management and staff.

Under current rules, the five largest economies (and therefore the 5 largest shareholders), each appoint one ED, as do China, Russia and Saudi Arabia. The remaining 16 seats are divided among the remaining 180 countries. Western Europe has a total of 8 chairs (9 when Spain is representing the constituency of Mexico and Venezuela), while 46 Sub-Saharan countries have 2 chairs. The Managing Director (MD) is the Chair of the Board and the Employee of the Board and the Chief Executive Officer. S/he is selected by the major Western European countries, approved by the United States (U.S.) and formally elected by the Executive Board. The MD selects the Deputy Managing Directors, who chair the Board when the MD is absent.

Voting shares and chairs all derive from the measurement of a country’s “economic size”, through a quota formula. These shares tend to determine how much each country contributes to the common capital of the Fund and how much each country may borrow from the Fund. The U.S. is the only single country with sufficient votes to block a Board decision when the issue requires an 85% majority. Ordinarily the Board decides matters by consensus.

Transparency

Despite the increase in IMF transparency through the public release of key documents, and the opening of the archives to researchers, the Executive Board discussions remain hidden, even with the release of Public Information Notices (PINs, now included under the general name of “Press Release”). Indeed, in response to complaints regarding the obtuse language of in PINs, the IMF provided a guide to “translating” them, explaining the significance of bland words that actually carried significantly different meanings, such as “some” versus “several” versus “many” that indicated the number of Executive Directors expressing certain positions. The Minutes of Board meetings are released after 5 years and are available through the archives; there are no verbatim transcripts of Board meetings. The citizen of a member country still cannot know what their Executive Director has said on any particular issue. Some EDs release their formal prepared speeches to national audiences; but not what is said in the context of a Board discussion. The Board recently agreed that IMF publications should be released in a more timely way, and while it still allows countries to exclude material, the newer standards seem to restrict such exclusions to genuinely “market sensitive” information. The bottom line is that material released by the IMF is sanitized, despite being characterized as a public, intergovernmental institution, funded by governments and therefore by taxpayers, that makes decisions that directly impact the lives of citizens in areas long regarded as the exclusive reserve of national legislatures.

Inclusiveness

Participation must be assessed on four different levels:

- In terms which include all member-states while retaining relative efficiency, the Executive Board constituency model is one deserving of replication in other international organizations.

- However, its execution has many failings: The IMF uses a façade of technical neutrality when discussing the quota formula used to allocate voting shares—and voice—commensurate with economic size of each member state. In fact, the formula groans under the weight of all the political goals it must serve, such as: not reducing any member’s share without their agreement, therefore tolerating quota factors that are inappropriate and/or duplicative; ensuring England and France are equal; recognizing that China is fast becoming the second largest if not the first largest economy, which the U.S. will not recognize for it would remove the U.S. veto and relocate the institution; mouthing support for the low-income countries without delivering. These tensions were evident in the outcomes of the 2010 Korean G-20 Summit which offered platitudes about protecting low income countries, insisted on European reduction of chairs by 2, and promised to double the income of the Fund. To date, the U.S. Administration has failed to secure Congressional approval for changes to the status quo, thereby putting IMF governance in a long-term stall, despite U.S. leadership in pushing for all of these changes in Korea. Ironically, these quota reforms emerged in large parts because of persistent complaints about the IMF’s democratic deficit, but always exclude population, or people, when calculating the size of an economy and thereby the corresponding voice of the member state.

- Participation also must consider management and staff: As noted above, the Managing Director has always been European and the First Deputy Managing Director an American. The remainder of staff and management are frequently of diverse nationalities, with a heavy emphasis on Europeans; their common denominator is orthodox economic education from select schools. Mid-level entry from other institutions is becoming less rare. Diverse thinking is also beginning to surface in Fund analytics; less so in Fund practice.

- Direct participation by Parliaments and affected peoples does not happen but new efforts are afoot to reach out more effectively to civil society organizations. To date, the Fund sets the agenda and the timing.

Accountability

In order to ensure that Board, Management and Staff adhere to the goals and best practices of the IMF, regular and reliable evaluations must occur. Fund managers evaluate the performance of staff and the IMF as an institution evaluates the performance of member states. However, once an Executive Director is selected (appointed by the largest economies; elected within constituencies which usually select the nominee of the largest member of the constituency), the Articles of Agreement and By-Laws provide no means whereby that ED can be removed for his/her two-year term, regardless of private or professional conduct. The EDs appointed by the 5 largest member states can be removed rather simply by a political decision, not necessarily the result of performance evaluation. There is no job description for an ED, nor criteria for selection or for assessing the execution of their tasks.

Since the selection of Dominique Strauss-Kahn in 2007, the Managing Director has an Executive Board-prepared description of the qualifications the person should bring, and a stipulation that the MD is bound by the rules of ethics for senior management and staff. In practice, those stipulations have no bearing on the selection or removal of an MD. Despite many promises that MD selection would be purely merit based, independent of nationality considerations, the fact remains that all MDs have been chosen from and by major European economies, with the approval of the U.S. There is no periodic performance evaluation of the MD by the Executive Board; the person remains MD so long as his/her political sponsors are satisfied with the person’s performance.

The Board of Governors exercises little oversight of the Executive Board as a body. Its meetings are largely ceremonial. The single committee of the Board of Governors is the International Monetary and Finance Committee (IMFC) which meets twice a year, and is allegedly an advisory committee but has powers well beyond advice. The G7 and now the G20 act as the de facto executive committee of the Governors, setting the agenda of the IMFC.

A positive aspect in IMF accountability is the Independent Evaluation Office (IEO), which the Executive Board established after the Asian Financial Crisis in 2001. The IEO is genuinely independent of Management, reports directly to the Executive Directors, sets its own agenda provided it does not review ongoing work. Regrettably, the Executive Board no exhibited substantial oversight over implementation of the IEO recommendations – which are approved by the Board itself. Management periodically reports generally that all Board-approved recommendations have been accomplished or are on schedule for a timely completion, even when recommendations are repeated in subsequent evaluations.

In sum, the Governors do not evaluate the IMF as a whole, nor does the Executive Board; the Executive Board does not evaluate the MD and ignores Management’s undercutting of the IEO, the single independent entity set up to evaluate programs and activities. Occasional internal self-evaluations by the Strategic Planning and Review Department are self-critical, but do not seem to result in policy or behavior changes nor rarely in punishment for any responsible individuals and never in compensation for those negatively impacted by wrongful policies or actions.

Occasional internal self-evaluations by the Strategic Planning and Revew Department are self-critical, but do not seem to result in policy behavior changes nor rarely in punishment of any responsible individuals; compensation for those negatively impacted by wrongful policies or actions is not possible.

Responsibility

The IMF maintains it is not possible to determine any causal connection between the policy conditions associated with receiving IMF funds and any subsequent pain or suffering endured by the residents of the country in question. This rationale rests first on the assertion that the chain of causality is too complex to be reliable. Second, the Fund cannot be held responsible for policies that are “formally” set by the government, in tandem with the IMF, but never as a contractual arrangement. Third, countries approach the IMF when they are already in extremis. They are in desperate economic straits, unable to receive help from any other source, and according to this rationale, are largely responsible for problems of their own making. If the country has been profligate in previous spending, and the IMF has them balance their budget, it is the prior profligacy that is to blame, not any austerity or other policy measures imposed by the Fund.

The Fund could be expected to conduct research on possible linkages, given the many complaints over the years about its programs from people and countries living with them. In 2002 the Boards of the IMF and World Bank jointly agreed on Poverty and Social Impact Assessments (PSIA). However, the IMF Board allocated minimal funding for this purpose, choosing to rely on World Bank research. The World Bank conducted extensive (taking about 18 months and costing roughly $100k each) in-country research by sector where there were Development Policy Loans, i.e., budget support. The IMF was largely dissatisfied with World Bank research as inappropriate (sectoral, not whole economy macro-economic, policies), too time-consuming, and too expensive. To its credit, the IMF Research Department has assessed the poverty consequences of large extractive industries in low income countries. Yet to be studied systematically are the poverty and distributional consequences of IMF tax advice to low income countries through advice accompanying regular Article IV Surveillance, loan agreements, or the technical assistance where the IMF is the international community’s lead organization, operating on the ground through regional Technical Assistance Centers.

Others take a different approach. Bradlow, for example, maintains that conditions associated with Fund programs are increasingly intruding on domestic policies, the classic terrain of national policies and national legislatures. Further, if the Fund “encourages” all its borrowers to reduce spending there is a cumulative effect, reducing the economic activity across borders. But the Fund traditionally has only considered the macro-economic activity of one country at a time. The Fund is beginning to conduct multi-country surveillance, primarily among advanced countries, in order to assess the cross-border effects of domestic policies. The Fund is also beginning to recognize the utility, if only as the last and temporary measure, of employing capital controls to manage inflows of hot money and to manage outflow of illicit money. Also, beginning with advanced economies, the Fund has suggested that austerity measures may be excessive and further stimulus may be needed. While the Fund is reversing its advice, is there no liability for the harm resulting from earlier advice.

Under current arrangement there is no option for individuals, communities, or countries that may have suffered harm from Fund promoted policies to register their complaints. Nor can they expect any compensation. The Fund maintains that everything is the government’s responsibility. An intergovernmental body, the IMF and its staff enjoy full legal immunity.

Overall Assessment

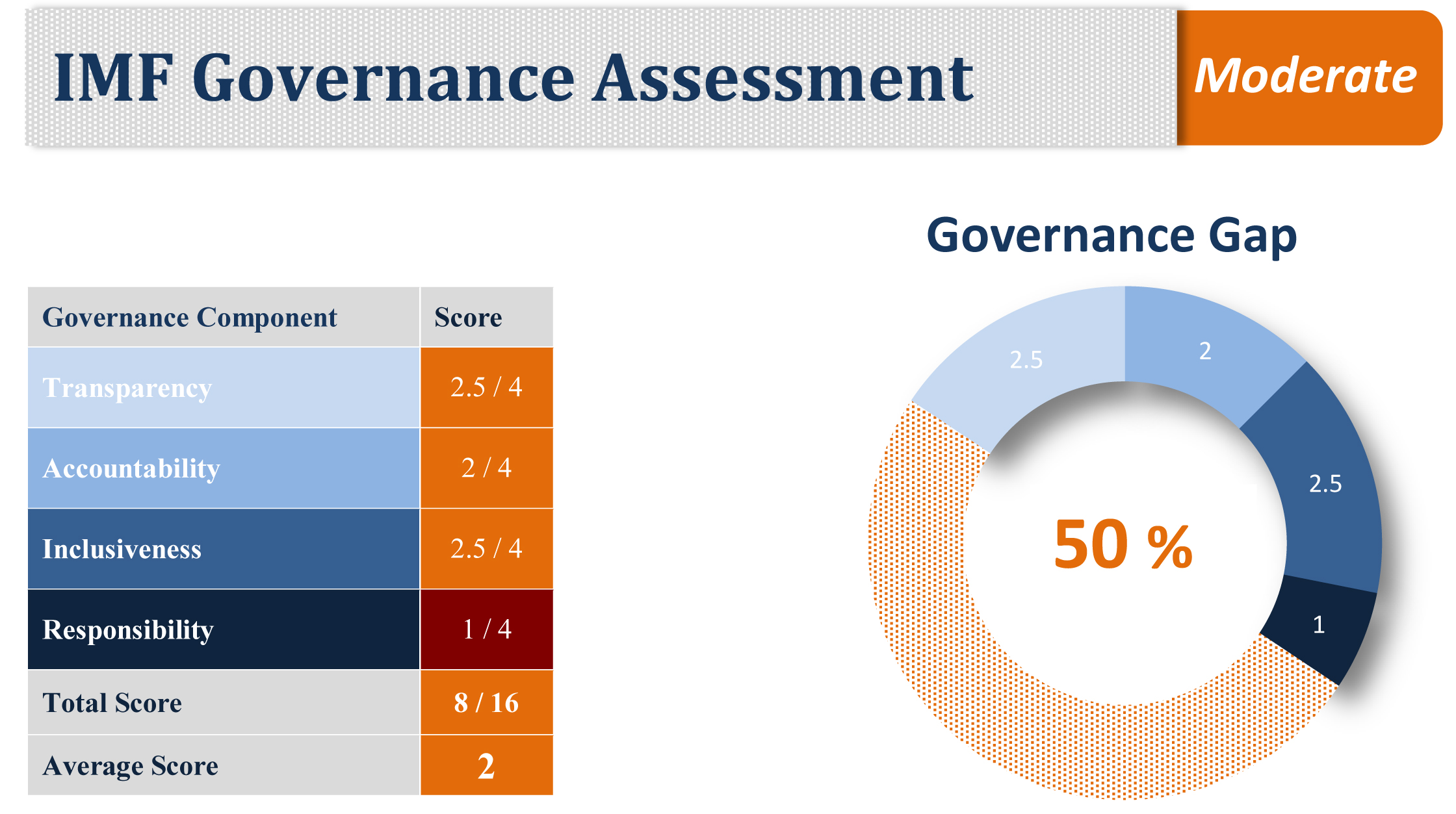

Transparency: The IMF release of information has increased over time but its basic decision making remains secret, as well as much that is related to its technical assistance [2.5].Inclusiveness: Changes to the quota formula in 2010 still left low income countries under-represented with Western Europe over-represented; despite the lack of progress with the U.S. Congress and the miles yet to be covered, progress has been made [2.5];Accountability: IMF Accountability requires significant reform; however over the years it has seen improvements [2];Responsibility: There are no mechanisms for affected people to complain, nor does the IMF track complaints from injured parties, arguing causality cannot be proven. This is unacceptable.

IMF Impact

Author: Matthew Martin, Development Finance International

Introduction

The IMF’s mandate is to: promote international monetary cooperation, maintain relatively stable exchange rates, and balanced growth of international trade. The combined results are expected to be the promotion and maintenance of high levels of employment and real income. The IMF is also to provide member countries with financial resources to correct payments’ imbalances and ensure that the programs adopted do not adversely affect the poorest sectors of society.

Through its economic surveillance, the IMF tracks the economic health of its member countries, alerting them to risks and providing policy advice. It also lends to countries in difficulty, and provides technical assistance and training to help improve economic management. This work is backed by research and statistics. In this way, it helps the international monetary system serve its essential purpose of facilitating the exchange of goods, services, and capital among countries.

This assessment of IMF impact focuses on its relations with low-income countries (LICs) through lending programs and policy advice.

The IMF lending facility for LICs, the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) was established in September 1999 to make the objectives of poverty reduction and growth more central to lending operations in its poorest member countries. Several reviews of the PRGF have taken place since 1999, but in 2010, in the aftermath of current financial crisis, the PRGF was revamped and renamed the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT). Its three types of loans [the Extended Credit Facility (ECF), the Rapid Credit Facility (RCF) and the Standby Credit Facility (SCF)] are to promote poverty reduction and growth. The IMF’s Policy Support Instrument (PSI) can also endorse policies ─ thereby giving those policies the “IMF seal of approval” so important to donors and investors ─ without lending funds. As of August 2013, the IMF had lending programs with 21 LICs, and PSIs with a further 5.

One of the biggest problems for LICs is that the IMF has had woefully insufficient funds to help them with balance of payments difficulties. Its resources for low-income countries were doubled by the G20 in 2009, allowing it to lend US$3.8 billion a year, but that has gone back to the pre-crisis US$2 billion a year. The problem for individual countries remains that loans to them are limited to a percentage of their membership quotas in the IMF. Quotas have fallen increasingly behind growth in world GDP, trade or capital flows, and are now only a very small part (often under 10%) of the amount an individual country needs to combat a crisis, not at all commensurate with the high influence the IMF has on country policies since many donors make their aid flows dependent on an IMF “seal of approval”.

Under ECFs, RCFs, SCFs, and PSIs, the IMF and the country agree to a set of “policy conditions” or “conditionalities” to improve economic policies. These have been narrowed somewhat in recent years to focus on the IMF’s core mandates (fiscal issues [tax, spending and debt]; monetary policy and credit availability; financial sector reform and stability; and balance of payments/external sector) while removing other conditions such as privatizations and trade liberalizations. In what follows, the IMF is assessed on its overall achievement of the “growth” and “poverty reduction” aims of the PRGT, as well as its main areas of conditionality.

Growth, Poverty Reduction and Inequality

The way the IMF helps countries design macroeconomic policy has a key impact on growth, and on reducing poverty and inequality. The IMF sets specific growth targets in its programs, based on what it regards as achievable given the level of financing available to the country, the potential impact of large growth-oriented projects, and possible trade-offs between growth and inflation.

Recent analysis by Oxfam has shown that real GDPgrowth in IMF program countries increased sharply between 2001 and 2008, after the introduction of the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility, though it was only slightly higher than in non-program countries. However, it has slowed since the global economic crisis, and is now below levels in non-IMF program countries. In addition, these growth rates (averaging 5% from 2001 – 2008, but only 4% since 2009) are considerably below the 7% levels which the UN has said countries need to halve poverty and thereby reach Millennium Development Goal (MDG)-1.

IMF and independent assessments have indicated that IMF programs have also been associated with poverty reduction. Poverty has fallen almost twice as fast in IMF program countries (by 20 percentage points) compared to non-program countries, with accelerating progress during the PRGF period. Data are not recent enough to assess progress since the crisis.

However, IMF programs have managed to assist only marginally with inequality. Gini coefficients stayed high in IMF program and non-program countries, and rose in both groups in 1990-2000. Although they fell slightly in program countries after the PRGF was introduced, the difference with other countries was marginal.

Overall, IMF programs are not consistently correlated with significantly higher growth, or (in the last decade) with faster falling inequality, than non-IMF program countries. IMF program countries do seem to show faster poverty reduction, though this advantage has diminished in the last decade. As a report for a Norwegian Coalition of NGOs has indicated, there is “only very limited evidence of an enhanced focus on growth and poverty reduction”under the PRGT since 2009, compared to its predecessor PRGF.

This analysis is only an initial assessment, because data for poverty and inequality remain very poor. However, it is striking that the IMF has not done any in-depth multi-country analysis of these issues, and has acknowledged that its analysis of growth and anti-poverty/inequality strategies in LIC programs and surveillance is insufficient. Much more needs to be done to ensure IMF programs produce faster growth and reduced poverty and inequality – as intended by the “enhanced focus on growth and poverty reduction” mandated by the IMF Board when the PRGF and PRGT were established. These efforts represent a major challenge for the IMF in the post-2015 (MDGs) global development agenda.

Fiscal Policy (revenue and tax, spending; and debt and aid)

On tax, the IMF has invested much policy advice and technical assistance on increasing revenue collection levels as a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP), with some success. However, it has been criticized for focusing excessively on “efficiency” to mobilize maximum revenue, and not considering the “equity” of its policy advice (i.e., whether the tax is progressive; or is a level playing field for foreign and domestic enterprises). In addition, it has had a strong preference for reducing revenues from trade taxes, in line with broader global trends towards trade liberalization. As a result of these two factors, there has been an increase in LIC reliance on “indirect” taxes on consumption (sales taxes and value-added taxes), which are likely (unless goods consumed by the poor are exempted) to be regressive – i.e., to hit poorer citizens harder. In some countries, the IMF has also suggested reducing higher rates of “direct” taxes (corporate and individual income tax), which has reduced revenues from these sources. However, this latter trend has been moderating in more recent programs, with some countries increasing the share of revenue coming from direct taxes.

During the 1990s, the IMF often agreed with encouraging low-income countries to provide tax holidays or exemptions for investors, in order to encourage investment. However, over the last decade, especially for countries which have become established investment destinations, the IMF has been increasingly suggesting abolishing exemptions and holidays, and renegotiating contracts which provide these, especially for extractive industries (mining and petroleum). Yet it has not adjusted its conditionality or tax technical assistance, and has been reluctant to criticize other agreements such as bilateral tax and investment treaties, or exemptions for donor or NGO funds, which are also reducing developing country revenues.

On national spending programs: There has been a marginal increase in education and health spending under IMF programs between 1985-2009, largely due to the Fund’s requirement that debt relief funds be spent on these sectors. The IMF has monitored levels of social spending, though there are major problems with the methodology. However, several recent independent reports have demonstrated that since the global economic crisis, spending on MDG-related sectors (which range from halving extreme poverty to halting the spread of HIV/AIDS and providing universal primary education) has not performed as well for countries with IMF programs compared to other countries. This is partly due to the fact that after an initial stimulus response to the crisis in 2009-10, overall spending levels in IMF programs has stagnated or fallen as a proportion of GDP. Given that spending levels in most countries are also far short of those needed to attain the MDGs, the IMF will need to dramatically increase its focus on mobilizing additional revenue and financing and enhancing MDG-related spending, if LICs participating in IMF programs are to meet the MDGs and post-2015 goals.

Another key spending issue has been the balance between investment and recurrent spending, and especially a tendency by IMF missions to recommend reductions in recurrent spending, through cuts in real wages, or reductions of staffing levels, including in the social sectors. The IMF made a specific undertaking not to include wage bill cuts as specific performance criteria in programs except in exceptional circumstances, yet continues to suggest them as part of policy discussions in almost all countries, resulting in a predominance of wage bill cuts in recent programs.

However, the major current labor issue (provoked in part by greater public discussion by IMF management of the need for “job creation and inclusive growth”) is the lack of a clear IMF policy to promote employment, balancing this with the objective of reducing inflation. Critics (and the Fund itself) have noted the IMF’s past and current preference for labor market “structural reforms” and greater flexibility, which is also reflected by its systematic use of the controversial World Bank “Doing Business” labor policy index in its programs, and measures in 32 current programs. Critics and the Fund have also indicated that there is no evidence or consensus in analysis that such reforms work to increase employment or income of workers.

The most recent IMF analysis of these issues recommends “more systematic diagnostic analysis of growth and employment challenges and identification of the most binding constraints to inclusive growth and jobs so as to provide more tailored and relevant policy advice; more systematic integration of policy advice on reforms of tax and expenditure to create conditions to encourage more labor force participation, including by women, more robust job creation, more equity in income distribution, and greater protection for the most vulnerable; and enhanced advice on labor market policies based on empirical evidence and greater collaboration with the World Bank, OECD and ILO on the impact of these policies on growth, productivity, job creation, and inclusion.” However, though the Fund has prepared a “toolkit” for work on growth, labor and inclusion issues for country teams, there is little evidence yet of a change in policy recommendations to country authorities.

Debt: From a low-income country perspective, relief on debt to the IMF, agreed in 2005 under the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI), was very welcome. There has since been a lengthy discussions with the Fund (and the World Bank) about its conditionality on borrowing by LICs, as reflected in the LIC Debt Sustainability Framework (DSF) and the IMF program borrowing ceilings. Both the DSF and the borrowing limits policies have been improved and made somewhat more flexible. However, many low-income countries still feel that they are too constraining in the context of massive infrastructure financing needs and shortages of aid financing.

The IMF has also been playing a key role in coordinating efforts at international debt relief, especially through the Enhanced Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC) and MDRI initiatives, in advising other creditors on how much relief is needed to make LIC debt sustainable. HIPC processes represented a vast improvement over earlier practices, in that the relief was based more on country needs, and involved a wider range of creditors. However, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) and some creditor and debtor governments have long called for a more comprehensive debt resolution mechanism which would be independent, fair and transparent, and more clearly legally binding on all creditors.

The IMF made some initial efforts in 2003 to place itself at the head of such a process through a Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism (SDRM), but failed to receive majority Board support for such an initiative, and has since backed away from such fundamental reforms. A recent IMF analysis acknowledged that debt restructurings have often been too little and too late, thus failing to re-establish debt sustainability and market access in a durable way, but indicated that an SDRM would not command support, and recommended only improved analysis, exploring ways to avoid having Fund resources bail out other creditors, and measures to reduce restructuring costs and increase commercial and non-Paris Club government creditor participation.

Many independent sources also question whether the IMF should lead on this issue, given that in many cases it is itself a creditor of the debt-burdened country, and argue that the UN is better placed to host such initiatives and consider fully the impact of the debt burden on reducing MDG-related spending.

Monetary and Counter-Inflation Policy

IMF programs have historically targeted inflation rates in all program countries; for LICs the rate has been well below 5% over the medium-term, which many argued was excessively deflationary and compromised chances for growth. In recent years there has been some evidence of greater flexibility, with most programs aiming for between 3% and 7%, allowing greater flexibility for monetary and fiscal expansion. However, there remain widespread criticisms of excessively restrictive monetary policy, resulting in insufficient credit for the private sector and high interest rates. For intense, heated debate see writings by Action Aid and the Center for Economic Policy and Research (CEPR).

Financial Sector Reform and Stability

The IMF plays two roles in financial sector reform and stability. At the global level, it produces analysis (and provides advice to the G20) on potential risks to global macroeconomic and financial stability from financial developments – principally through the “Global Financial Stability Report” (GFSR). It was heavily criticized for its failure to foresee the global financial crisis and has since beefed up its analytical and surveillance capacities. Its reports and speeches by the Managing Director regularly criticize the slow pace of G20 agreement and implementation on financial sector regulations, and place more stress on potential downside risks. For example, the last GFSR warned of a scenario in which “a global financial crisis could morph into a more chronic phase, marked by a deterioration of financial conditions and recurring bouts of financial instability,” and spoke strongly of the need to reinvigorate the regulatory reform agenda, especially on banking, over-the-counter derivatives, accounting and shadow banking, and to ensure coherence rather than fragmentation among new national-level regulatory measures.

At the national level, the IMF is the main organization responsible for assessing financial development and stability in LICs, through its Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP), and for seeing that Financial Stability Board (FSB) recommendations and global regulatory standards and codes (such as Basel III) are implemented in LICs. However, as discussed in the chapter on the FSB, this agenda is set by developments emanating from the global level, leading to over-emphasis on banking sector reform and concerns about access to banking services, and insufficient emphasis on other non-bank financial institutions with a longer-term and more stable investment perspective, such as insurance, pension funds, micro-finance, or community-based financial systems. The Fund’s work is also moving at the same slow speed as FSB global discussions in terms of adapting recommendations to the post-crisis environment, especially in LICs.

Balance of Payments Policies / Capital Controls

Note: This issue overlaps with inflation, given inflation results from capital inflows from US especially (QE2, QE3)

A final controversial issue has been the IMF’s attitude toward controls by LICs on capital flows. The Fund’s Articles of Agreement ensure that “Members may exercise such controls as are necessary to regulate international capital movement. Efforts to amend the Articles of Agreement to require financial liberalization failed in the aftermath of the current financial crisis. During the 1990s and early 2000s, through its own research, the Fund began to urge caution in the scale, speed, and sequencing of capital account liberalization, even as most country programs supported relatively rapid liberalization, and underplayed its risks. It also largely failed to provide any advice to source countries providing private capital flows to introduce policies which might have reduced their volatility.

Since 2005 and especially after the global financial crisis, there has been a gradual redefinition of the IMF position. This culminated in a new “institutional view” in November 2012 and staff guidance note in April 2013, which indicated that the IMF would not include conditions on capital account liberalization in its programs. On the other hand, these have been criticized by developing countries and CSOs for: emphasizing the need for a continued strategy in most countries of capital flow liberalization, while conceding that “staff advice should not presume that full liberalization is an appropriate goal for all countries at all times”; putting severe limits on both the circumstances and the design of any controls or other measures to reduce volatility; and advocating only limited discussions with source countries. In practice, however, for most low-income countries, this is no longer a burning issue, as they have already liberalized capital flows. Instead, they need advice on when and how they should re-introduce controls. Paradoxically, when they seek IMF advice, they still encounter opposition to any use of capital controls.

Overall Assessment

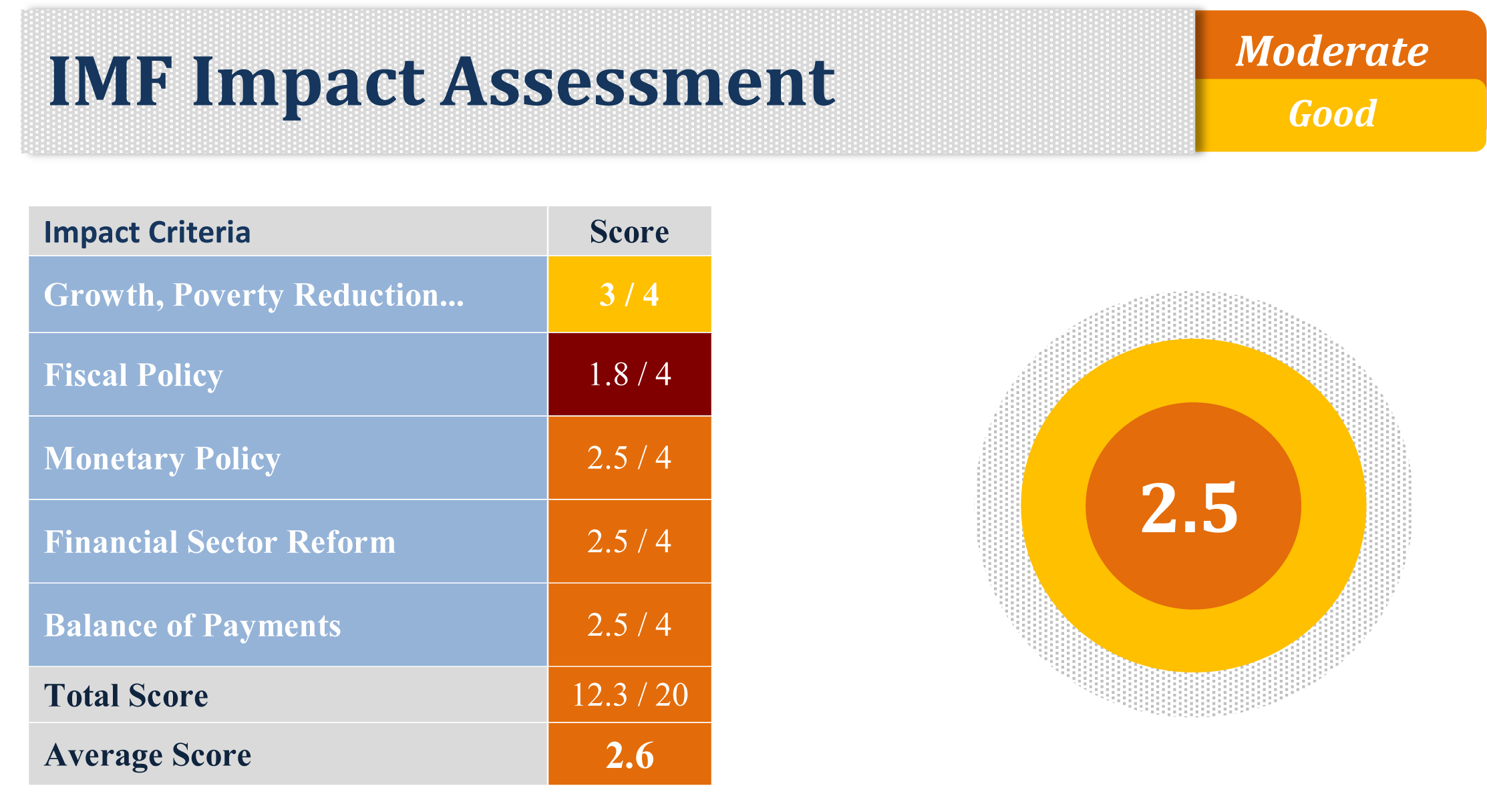

The overall assessment of IMF impact should be seen as slightly positive on growth and poverty reduction; negative on inequality and inclusion; negative on spending; negative on tax; positive on reducing debt; mixed on broader debt resolution; and mixed on financial and external sectors. In all of these areas, the Fund appears to be making efforts at improvement and therefore its future impact has a positive outlook at this time.

The report can be accessed through the attached link: