Global Financial Governance & Impact Report 2013: Tax Rule-Making Bodies

Tax Governance

Author: Jo Marie Griesgraber, New Rules for Global Finance

Abstract

International tax rule-making has become a controversial topic as the United State and the Eurozone both cut programs and begin to prosecute tax avoiders and evaders. The increased public awareness of multinational corporations’ (MNCs) ability to transfer profits to tax havens increased pressure on politicians to act. Development organizations have put the human face on people who are harmed by these arrangements. This paper describes the status quo non-system that prevails where three international organizations–the OECD, the IMF, and the UN Tax Committee—all claiming leadership of the international tax “system.” John Christensen’s words apply: where everyone is in charge, no one is in charge. The paper is organized as follows: the first section presents a short introduction to each of the three actors, followed by a scrutiny of the three institutions’ levels of transparency, inclusion, accountability, and responsibility. The conclusion assigns scores for the quality of governance at each of those levels.

Introduction

The principal institutions for international tax rule-making are: the OECD, the IMF, and the UN Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters (UN Tax Committee).

OECD: Since 1956, the Committee on Fiscal Affairs (CFA) of the Organization for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC) (now called the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development or OECD) has managed international tax policy coordination. Currently the OECD has 34 member-states, expanding beyond the original Western European members, to the US, Canada, Chile, Japan, Mexico, South Korea and several Eastern European members. The OECD claims partnerships with all the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), although other than Russia, have to date declined to join. The OECD has developed a “Model Tax Treaty” plus commentary to guide countries in their bilateral tax treaties. Treaties based on this Model are the only legally binding international tax agreements.

For international tax matters, the OECD’s key role is in transfer pricing. The basic theory supporting the OECD’s work in this area is that the subunits of a multinational corporation (MNC) are independent entities and the transactions between them can be valued at market prices. This fictive underpinning has led to continued evolution in made-up data bases to estimate “true market prices”, and 5 methods for determining market prices. These complex methods facilitate the ability of MNCs to hide or transfer their costs and profits to avoid paying taxes anywhere.

The OECD and G20 refer to the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes (Global Forum) as “the premier international body for ensuring the implementation of the internationally agreed standards of transparency and exchange of information in the tax area.” A creation of the OECD, Global Forum’s original members of the Global Forum were tax havens and OECD countries seeking common ground on transparency and information exchange. They produced the Tax Information Exchange Agreement, which provides for information on request. The Global Forum was restructured in September 2009 in response to the G20 call to strengthen implementation of these standards. It now has 120 members.

Most recently, in response to G20 requests, the OECD has outlined actions to address the problem of “Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS),” and has proposed a 3-year program of study leading to recommendations to repair the ineffective international system, but not to overhaul it.

IMF: The IMF’s governance is described in detail in the IMF Governance essay in this report. Its role in international tax policy processes is largely in research and capacity building. The IMF co-authored with the OECD, UN and World Bank, “Supporting the Development of More Effective Tax Systems,” A Report to the G-20 Development Working Group. In response to the G20 BEPS agenda, the IMF prepared an outline of its own role and agenda in the field of international tax policy.

UN Tax Committee: The UN International Conference on Financing for Development (Monterey, Mexico, 2002) agreed to elevate the Ad Hoc Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Mattersto a more permanent Committee of Experts (UN Tax Committee) under the UN’s Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), with a small Secretariat in the new Financing for Development Office located in the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA). Under this Committee of Experts, UN countries nominate tax experts who serve in their personal capacity for a 5-year term; the UN Secretary-General selects individuals from among those nominated. Experts tend to be evenly distributed among OECD and non-OECD countries, men and women, North and South. On the basis of the 39 nominations presented by Member States in July 2013, the Secretary-General appointed 25 new individuals to the UN Tax Committee for a term beginning on the date of notification of such appointment and expiring on 30 June 2017. English is the Committee’s working language. The Committee meets once a year for 5 days in October in Geneva; meetings are open to observers, who may be recognized by the chair to raise questions or comment on the Committee discussion, as well as to serve on Committee subcommittees. The Committee has a budget for only this meeting; all other expenses must be borne by the individual or by the sending country, even though the individual does not formally represent any government and agreed documents are not inter-governmental agreements.

Transparency

In the discussion of Transparency the focus will first be on the transparency of the institutions themselves, and then on the quality of transparency of the policies each designs. Of the three institutions–the OECD, with the Global Forum, the IMF, and the UN Tax Committee–the best performer is the UN Tax Committee. The following provide brief summaries in support of this conclusion:

The OECD is relatively transparent. Research and policy papers are generally announced ahead of time. However, non-member-governments have limited opportunity to participate in the generation of papers; staff are accessible; the for-profit private sector seems to have greater access and influence than the non-profit sector. Draft documents are not public, nor are public comments solicited. In turn, the Global Forum itself seems to be transparent in its agenda and meeting announcements.

The IMF is the lead almost-global institution charged with capacity building in tax policy. The IMF maintains it responds to the demands of its clients: whatever help governments request, the IMF provides, so long as it is within the mandate of the Fund. Little data, if any, exists to substantiate that claim. There are catalogs of IMF technical assistance offerings with short course descriptions. However, there are limited public assessments of the quality and utility of the courses.

The UN Tax Committee meetings are open to anyone who registers; its annual meeting dates and agenda are publicly available through the UN website. All papers and decisions are available online. Membership is formally available to all tax experts, provided they are nominated by a UN member government, and selected by the UN Secretary-General, on the advice of the Secretariat technical staff. The UN Tax Committee could become more transparent by establishing criteria for nomination and if the nominating process could be open to all, not just member states. The subcommittee meetings are announced beforehand.

Apart from institutional transparency, do these institutions promote policies that encourage transparency?

The OECD attempted to tackle the international tax haven problem by “blacklisting” offenders. This initiative halted with the opposition of the new US President, George W. Bush. The OECD then did an about-face, inviting those same tax havens to design a treaty on information collection and exchange. This became the Tax Information Exchange Agreement (TIEA), a non- binding instrument whereby governments can request information about their citizens, but must specify the name of the individual and the institution within the tax haven, and the nature of the “offense.” Since tax havens cooperate in hiding the identity of the actual or “beneficial owner”, such treaties rarely provide information leading to prosecutions. Furthermore, any country that signs 12 treaties, is off the “blacklist”.

Both the OECD itself and its creation, the Global Forum, rely on peer reviews, and it is peer pressure that leads to countries implementing OECD and Global Forum standards.

Paradoxically, the OECD and Global Forum continue to promote the TIEAs to combat tax haven abuse, and the G20 has endorsed TIEAs as the standard for information exchange. However, under the TIEA, information exchange is not automatic.

“Any request for information under a TIEA must provide:

(a) the identity of the person under examination or investigation;

(b) what information is sought;

(c) the tax purpose for which it is sought;

(d) the grounds for believing that the information requested is held within the jurisdiction to which request is made; and

(e) to the extent know, the name and address of any person believed to be in possession of the requested information.”

Despite accepting the TIEA (which provides information upon request), the US has launched its own Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) program to require information from all foreign banks on all US citizens and green-card holders having accounts in those banks; the European Union moves ahead with its proposal for a Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base; the G8 endorsed automatic exchange of information relating to taxes and endorses disclosure of Beneficial Owners; and the September, 2013, Tax Annex to the St. Petersburg G20 Leaders’ Declaration, endorsed the development of a new global tax standard, namely, automatic exchange of information.

Inclusion

OECD has engaged with civil society through the Tax and Development Taskforce, since 2010. Those CSOs who have participated, usually as representatives of a broader collective of CSOs, repeatedly express frustration that their interventions are not listened to and there is scant evidence that the OECD has considered, much less incorporated, any CSO proposal.

Global Forum membership now stands at 120, and membership is expanding. Members pay dues based on the size of their economies. Despite assertions regarding its independence, the Global Forum is strongly tied to the OECD. Its Secretariat is staffed by both OECD and non-OECD personnel, but remains part of the OECD secretariat, answerable ultimately to the OECD Secretary-General.

IMF Staff and consultants provide technical assistance to member-government staff, in addition to fiscal policy advice that is part of every regular Article IV surveillance report, and of every review associated with an IMF lending arrangement. Developing country tax experts have expressed resentment toward the IMF, which asserts its power so forcefully, leaving many feel they have no option but to follow along or lose their jobs—or waste their time protesting.

As discussed above, formal participation in the UN Tax Committee is open to all who have expertise in tax administration and policy; but is limited by the number of seats (25), and to the nomination of a government and selection by the UN Secretary General for Tax Committee with the advice of the Secretariat in the Financing for Development Office. Representation by geography and gender has been generally balanced. Any interested person willing to commit the time and energy to participating is generally welcome so long as they are knowledgeable, courteous, and can cover their own costs. Observers have been involved in writing reports and doing research used by the Committee or any of its subcommittees. This openness therefore benefits those with access to independent resources, and results in extensive and intensive participation by the for-profit sector. Even members from developing countries without access to travel funds are de facto excluded from subcommittee meetings. Participation is also restricted because of the exclusive use of English.

Accountability and Responsibility

Given the decentralized, ad hoc nature of international tax rule-making and implementation, there are no firm rules made by the consensus of the governed, for the common good, to which all conform. Instead:

- all implementation depends on decisions at the national level;

- the rules, such as they are, depend on institutions dominated by the largest economies (IMF and OECD), and those rules protect their national interests;

- the most powerful private enterprises have shaped national laws, and permeate the OECD processes to minimize their tax payments;

- secrecy jurisdictions or tax havens exist by the design of the major financial centers, and enable funds to return to the market without paying taxes, or revealing who benefits from the wealth.

- Tax bureaucrats are out-numbered and under-paid compared to the armies of professionals (lawyers, accountants, lobbyists) who work to establish and maintain the current system.

Challenging these arrangements are:

- The declaration of the G8 in support of greater transparency of Beneficial Ownership

- The clear preference of the G20 for automatic exchange of information

- The assignment to the OECD by the G20 to work on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting

- The commitment by the IMF to research Unitary Taxation, as a frontal challenge to the “Arms-Length Principle” of OECD transfer pricing chaos.

Indeed, the IMF, has worked with developing countries to renegotiate contracts with corporations involved in the extractive industries (mining, oil, gas, sometimes forestry). In the Annual Meetings of the Bank and Fund for October 2013, the Fiscal Affairs Monitor will detail the large gap between the taxes claimed by advanced countries from extractive industries, compared to the tiny share received by developing countries.

The Swiss Bankers Association apologized for facilitating tax fraud. Could this be a harbinger of things to come?

There is no conversation yet about a World Tax Authority where common regulations can be designed—except at a recent event sponsored by Tax Justice Network at London City University in July 2013. Ten years ago a similar group articulated the need for automatic exchange of information, transparency of beneficial ownership, making a tax offense grounds for criminal prosecution under international anti-money laundering treaties. The 2013 TJN meeting also declared the need to replace transfer pricing with unitary taxation, perhaps even utilizing formulary apportionment to allocate where that de facto single corporation owed taxes.

In considering the total absence of Accountability and Responsibility of the OECD and IMF and their lead shareholders, any changes will come from public protest, and the articulation of viable and ethical alternatives from the think tanks and universities that work with the protesters.

The only place where developing countries have a voice is the UN Tax Committee. The major status quo powers need to empower this committee to become the embryo of a World Tax Authority, or to change the structure of the OECD tax units to become a constituency-based institution, where need and population as well as wealth and military might, constitute the bases for voice and votes.

At the same time, it behooves developing countries to come together to set their own priorities for tax policies and tax capacity building, possibly through regional or continental arrangements. By working more with neighbors and peers, and less with former clientalist arrangements, South-South learning can increase.

Overall Assessment

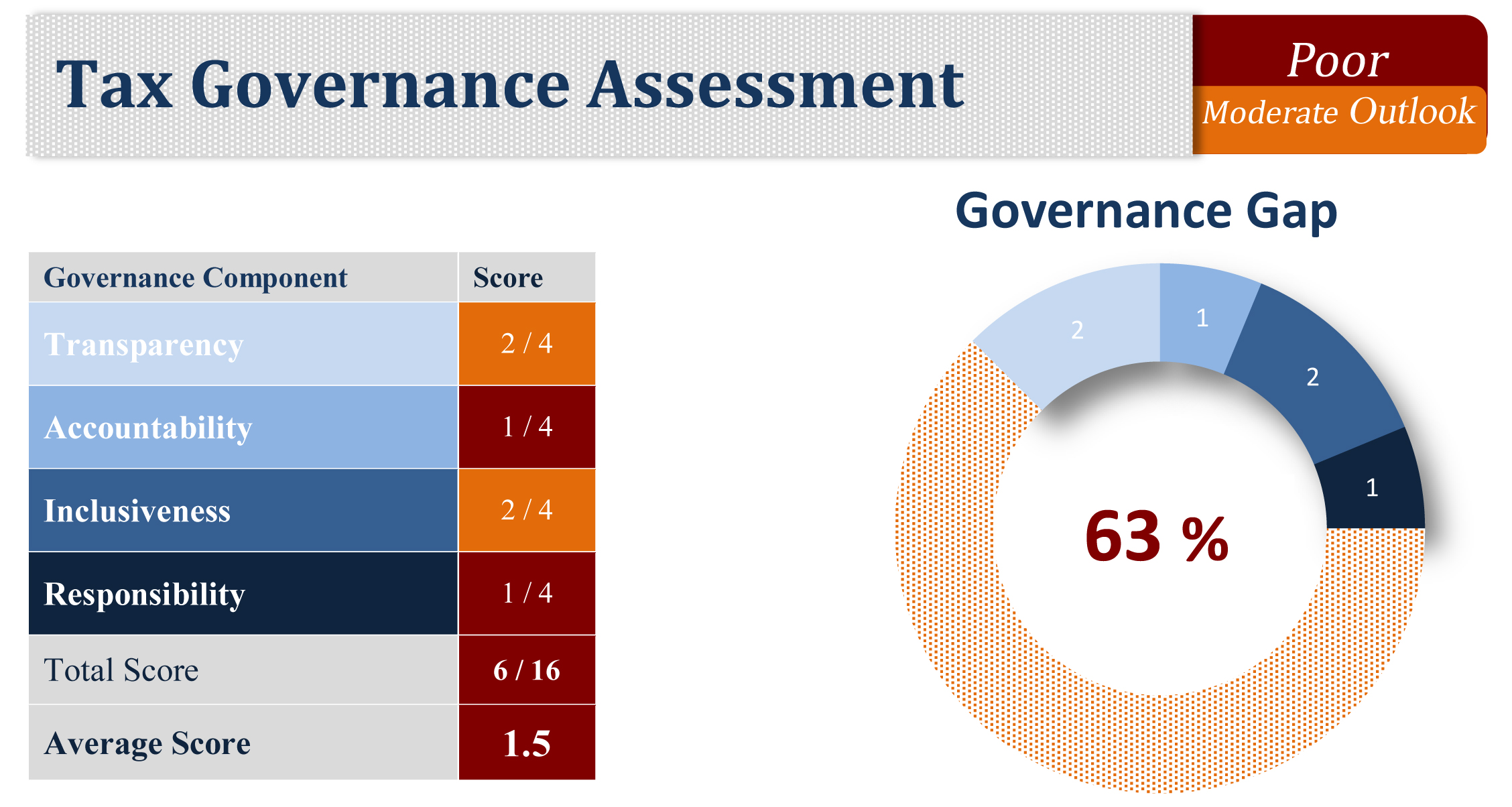

Transparency: since the IMF is scarcely transparent on its tax training, and the OECD is modestly transparent, and the UN is wholly transparent [2]. Inclusiveness: The IMF and the Global Form are inclusive of or provide representation for most governments, in practice the IMF Board and the OECD, the parent organization of the Global Forum, are controlled by the major powers for their agendas, with the smallest participation of civil society. The UN Tax Committee, not being an inter-governmental body but a gathering of experts in their individual capacities, does not have a representative function; it does permit all interested and competent parties to attend, inadvertently favoring those with access to independent funding [2]. Accountability: There are neither mandates nor institutional arrangements that ensure that institutions or their leaders are answerable for their performance [1]. Responsibility: Without formal procedures for holding any of the institutions to answer for the consequences of their actions or inactions, nor any arrangements for compensating those harmed, nor even procedures to receive complaints, this score would itself be too generous. However the promised work on BEPS by the IMF and the OECD, plus the IMF’s promotion of greater tax fairness from the proceeds of extractive industries to developing countries are hints of redeeming behavior [1].

Tax Impact

Author: Jo Marie Griesgraber, New Rules for Global Finance

“They say that the Ancient regime in France fell in the 18th century because the richest country in Europe, which had exempted its nobles from taxation, could not pay its debts. France had become … a failed state. In the modern world the nobles don’t have to change the laws to escape their responsibilities: they go offshore.” Nicholas Shaxson

The subjects of every state ought to contribute toward the support of government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities; that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state. Adam Smith

Introduction

The governance structure of the separate institutions that collectively formulate “global tax policy” misses a core element of the world’s taxation system: the “offshore” tax havens or secrecy jurisdictions. Typically these are small nation-states that have structured their tax policies to maximize secrecy, to facilitate hiding the true origins, destinations, and ownership of funds that can then be recycled to the major finance centers or returned to their countries of origin, free of any identifying markers. Nicholas Shaxson documents the origins and purposes of this system in his eminently readable Treasure Islands, while Tax Justice Network’s (TJN) Financial Secrecy Index (FSI) documents the number and opacity of “the usual suspects” as well as such on-shore facilitators as the states of Delaware and Nevada. These webs of secrecy must be included in any comprehensive and candid assessment of how the global tax system actually operates. These arrangements place formal rule-making in the hands of defenders of the status quo, while enveloping the actual machinery in fog and darkness. The size of these shadow monies is astounding:

A significant fraction of global private financial wealth…at least $21 to $32 trillion—has been invested virtually tax-free through the world’s still-expanding black hole of more than 80 ‘offshore’ secrecy jurisdictions.”

Impact of Tax-Rule Making Bodies

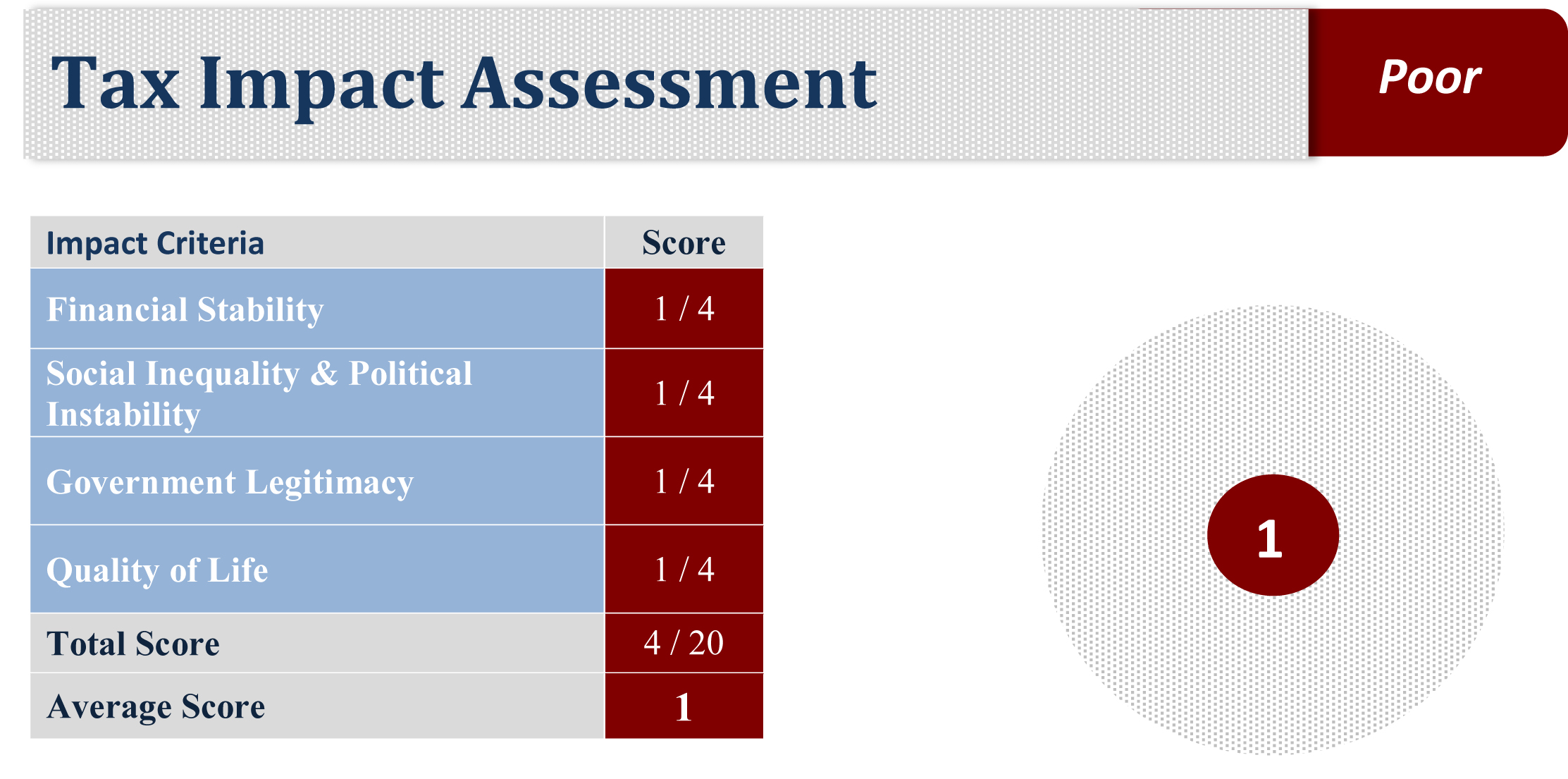

The international tax rule-making bodies that are either controlled by status quo powers (OECD, IMF) or deliberately weakened by them (UN Tax Committee), plus the network of secrecy jurisdictions, combine to:

1) damage global financial stability;

2) erode political stability by worsening social inequalities;

3) undermine the legitimacy of national governments, even long-standing democracies; and

4) reduce the quality of lives of a majority of the world’s population, while cutting short the lives of the most vulnerable.

Global Financial Stability: Financial secrecy and global markets

*Except taken from “Tax Us If You Can” 2nd Edition, Tax Justice Network

Fair international trade has the potential to generate tremendous economic growth and spread benefits across global society – but it has failed to live up to its promise. Cross-border finance has been revealed, especially since the latest crisis, to be especially problematic. Secrecy is among the most important reasons for these giant failures: capital flows in ever greater volumes around the globe, but the necessary information about that capital is blocked.

Secrecy jurisdictions are at the heart of the global economy. The top 12 “dirty dozen” jurisdictions that the FSI [Financial Secrecy Index] identifies as the most important providers of financial secrecy hold a staggering four fifths of the share of the global market of trade in financial services. Over half of banking assets and liabilities are routed through secrecy jurisdictions, more than half of world trade passes (on paper) through them; virtually every major multinational company uses secrecy jurisdictions for a variety of unspecified purposes, and well over USid=”mce_marker”0 trillion of private assets are held in offshore structures to evade and avoid taxes worldwide.

Secrecy jurisdictions are not a peripheral issue but one of the most important facets of globalized financial markets.It has long been held that free market capitalism requires the free flow of information to reduce risk and strengthen efficiency. Investors, regulators, tax authorities, economists, civil society, and many other groups and classes of people require this information for markets to work effectively. The FSI, however, suggests that secrecy is at the heart of contemporary global financial capitalism.

Secrecy distorts markets by shifting investments and financial flows not to where they will be most productive, but to where they can acquire the greatest gains from secrecy, such as the ability to engage in tax avoidance and evasion, say, or to escape financial regulation or criminal laws. It hinders effective regulation and law-making of all kinds, and enables insiders to reap the gains from global markets while shifting the costs and risks on to the shoulders of others. The result of such distorted and corrupted markets is a world of steepening inequality, rampant crime and impunity for élites in rich and poor countries alike. …

Despite regular protestations to the contrary, secrecy jurisdictions played a central role in fostering the conditions for the latest global financial crisis. They have also served as the main cross-border transmission belts for shocks and contagion during the various stages of crisis.2

Social Inequality & Political Instability

Increasing global inequity involves unequal distribution of wealth between and among countries, as well as within countries; between the financial sector and the real economy, and between those who make their money moving and those who earn salaries or wages that can be tracked and taxed readily with every weekly or monthly paycheck. TJN describes the connections between political (in)stability and social (in)equalities:

With the bottom half of the world’s population together possessing barely 1% percent of global wealth while the top 10% owns 84%, economic inequality is widely and increasingly recognized as a problem in its own right. Research shows that more unequal societies tend to experience slower growth, higher political instability, and a wide range of negative health and social outcomes, as [explained below]

Why inequality is a problem and causes problems

* Except taken from “Inequality: You Don’t Know the Half of It,” John Christensen, Nicholas Shaxson, Nick Mathiason

A number of recent studies have focused on correlations between income inequality and a range of social and economic problems. Perhaps the best known is The Spirit Level by Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson. They found that people in more equal societies are likely to live longer, to achieve higher grades at school, to enjoy social mobility, and to suffer lower rates of teenage motherhood, and to enjoy child well-being. [They are also] less likely to experience mental illness, to use illegal drugs, to be imprisoned, to suffer obesity, and to suffer violence. This study has been widely referenced.

A 2011 study by Isabel Ortiz and Matthew Cummins for UNICEF found that for 141 countries where inequality could be measured, those with rising inequality tended to grow more slowly over the period studied (1990-2008), and this “strong negative correlation between high inequality and high growth” remains intact for developing countries alone. They also found that inequality is strongly associated with political instability.

There is also evidence that inequality was a causal factor behind the global economic and financial crisis since 2007/8. Much of the ‘subprime’ borrowing patterns of low-income households, for instance, was driven by economic inequality stimulating consumption and higher borrowing among lower income levels. This chimes with research by the U.S. economist James Galbraith:

“The evidence in the U.S. shows that the rise in inequality is associated with credit booms, which are often periods of sometimes great prosperity. One was in the late 1990s with information technology and one in the 2000s with housing, before everything fell apart. But this is also a sign of instability — the crash that follows is very ugly business. If we’re going to go forward with growth on a more sustainable basis, then controlling inequality and controlling instability are the same issue. One is an expression of the other.”

Stewart Lansley takes a similar view, focusing on what happens when a gap opens up between wages and productivity, when benefits from greater productivity flow to the richest section of society. This throws economies out of balance: purchasing power and consumer spending fall and the demand gap is filled by rising debt, which postpones the problem.

Power follows money, and extreme concentrations of wealth at the top of the income scale lead inevitably to disproportionate power and influence for the wealthiest members of society. So some of the most malign political effects of inequality stem from changes at the very top of the income and wealth distribution….

[T]he ability of the wealthiest members of society to put their money offshore gives them great power: the oft-heard cry of ‘don’t tax or regulate us too much or we will move to Geneva or London or the Cayman Islands” has been wielded to potent effect in recent decades in eviscerating financial regulations, forcing tax cuts on capital, and more.

But how do tax policies contribute to social inequality? The simplest explanation was uttered by Leona Helmsley before she was arrested for tax fraud: “only little people pay taxes.” This neatly captures the attitude of the largest corporations and wealthiest individuals, who have the wealth and the will to hire armies of lawyers and accountants to hide their wealth from the national tax collectors, and to provide a patina of legalism on their stratagems to evade or avoid tax payments. Some corporations maintain it is their responsibility to “their shareholders” to minimize tax payments. In the United States, but not unique to the U.S., lobbyists by the hundreds, even thousands, are paid by interested parties to meet with Congressional members and staff to support loopholes or tailored concessions for specific interests, or to block the closure of such loopholes.

The decisions of the OECD as well as national legislatures protect the wealth of those who already enjoy it. The ongoing discussion of “Base Erosion and Profit Shifting,” a G20 task handed to the OECD, persists in supporting the “Arms-Length Principle” (ALP) for determining the taxes paid by various branches (i.e., part of the same legal entity) of a multinational corporation. The Governance section of this publication will allude in depth on ALP and transfer pricing.

Money and profits are then routed to and through secrecy jurisdictions so the true beneficial owner cannot be identified, and end up usually back in the same financial centers whence they originated. Of course legitimate businesses are not the only ones using these machinations. So too are drug lords and human traffickers. Astoundingly, when U.S. banks are used for these purposes, entire Congressional delegations, such as for the state of Florida, protest stronger regulations and greater transparency. The Members of Congress depend on the banks for financial contributions and the banks depend on drug money for their profits.

Legitimacy of National Governments

When the wealthy do not pay their fair share of taxes, the tax bill is left to the less wealthy and the poor to cover the costs of government, public goods and the management of global commons—everything from defense, police, clean air and water, to schools and roads, and the earth’s shared natural resources. Without sufficient income, Detroit goes bankrupt and schools close, while its rich suburbs have wealth aplenty. These outcomes cause many to distrust governments, from the Right and from the Left. This arrangement is not inevitable nor is ever increasing inequality inevitable. Different policies can lead to different outcomes. As Paul Krugman recalls,

The great divergence: Since the late 1970s the America I knew has unraveled. We’re no longer a middle-class society, in which the benefits of economic growth are widely shared: between 1979 and 2005 the real income of the median household rose only 13 percent, but the income of the richest 0.1% of Americans rose 296 percent.

Most people assume that this rise in inequality was the result of impersonal forces, like technological change and globalization. But the great reduction of inequality that created middle-class America between 1935 and 1945 was driven by political change; I believe that politics has also played an important role in rising inequality since the 1970s. It’s important to know that no other advanced economy has seen a comparable surge in inequality – even the rising inequality of Thatcherite Britain was a faint echo of trends here.

Quality of Life & Life Expectancy

Assuming James S. Henry and his reliance on International Monetary Fund, World Bank, United Nations, central banks and national accounts data, is even close to accurate, the impacts identified here must be only the beginning of the story. The costs and inconveniences of lost tax income for advanced economies are obviously serious for their citizens. For people in the developing world, especially the most vulnerable citizens, the scale of losses from such resources can be life threatening. Obviously, the actual amounts – and the corresponding costs – can only be estimated. In 2008, Christian Aid’s research estimated the loss to developing countries at a mere US160 billion annually, or over 1.5 times the global aid budget. And what of the impact of this loss?:

Imagine the difference US$160 billion a year would make to the fight against world poverty: to health, education, sanitation, clean water and other services in the world’s poorest countries. It could fund the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals several times over, eradicate malaria and other deadly diseases, or it could help to build people’s resilience to ever more frequent drought and floods in the face of climate change.

In another 2008 publication, their estimate of the consequences was more specific:

The situation is stark and urgent. We predict that illegal, trade-related tax evasion alone will be responsible for some 5.6 million deaths of young children in the developing world between 2000 and 2015. That is almost 1,000 a day. Half are already dead.

More recently the Dutch Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations, also known as SOMO after its Dutch acronym, said “this year that the use of the Dutch tax system by multinational companies had cost €771 m in annual lost tax revenue for 28 developing countries.”

The public outrage against this non-system for international tax policy-making has been seen in boycotts in London (Amazon, Google and Starbucks), Occupy Wall Street, and the collapse of the Romney Campaign after his 47% comments , and now the formal apology of the Swiss bankers over facilitating tax avoidance and evasion.

Overall Assessment

Will we see a comprehensive global tax code mitigating the negative effects of tax havens around the world in the near future? Probably not. The regulatory framework continues to be too unspecified and regulatory institutions like the OECD, UN Tax Committee or IMF are unable to create a homogenous tax code and speak with a unified voice. Furthermore, as national tax codes are so diversified stemming from different kinds of influences of history, culture, and country-specific aspects, the probability to establish a global tax code in the manner of a one-fits-for-all approach will be rather unrealistic.

However the increasing public outcry and protest against MNC like Starbucks exploiting tax holes, are promising examples that a bottom-up approach might be more effective in the first step than a top-down. As MNC are dependent on consumers to purchase their goods and products, MNC will be more apprehensive to the public opinion and under pressure to implement fair and concise tax codes under the umbrella of Corporate Social Responsibility. However, on a policy level, international institutions have to foster further cooperation among national governments to establish a regulatory framework to close global loopholes.

The report can be accessed through the attached link: