Global Financial Governance & Impact Report 2013: World Bank

World Bank Governance

Author: Jo Marie Griesgraber, New Rules for Global Finance

Introduction

As intergovernmental bodies, the World Bank and IMF are models of inclusion in that all member states are represented through the innovative arrangement of the constituency system. However, that same system set up a permanent conflict: the Executive Directors are BOTH officers of the institution (according to the Article of Agreement, their “only” duty), and de facto representatives of specific countries/groups of countries.

The governance structure of the World Bank mirrors that of the IMF. Indeed, the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference spent much time designing the IMF, and as the time drew near to close the conference they simply assigned the same general structure to the World Bank. The allocation of votes among the Executive Directors (ED) remains tied to the allocation within the IMF. The principal differences in governance structures between the IMF and World Bank derive from the latter’s various facilities and the funding sources.

The World Bank Group is formally a group of five institutions: the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the International Association for Development (quadr), the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), and the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). This article will focus on IBRD and IDA, with occasional reference to IFC. The same Executive Board and President govern all the facilities. The IBRD is funded by a small amount of paid in capital from all member countries, commensurate with the size of their economy as measured by the IMF; then each country also pledges “callable capital”, which serves as a guarantee for the World Bank which secures most of its funds by borrowing on the private capital markets. It provides loans to middle income countries at slightly above the market rate for AAA bonds. The IDA loans to low income countries and its funds come from: 1) any excess the IBRD earns from interest payments beyond that needed for Bank administration, and 2) directly from the budgets of the donor or Part I countries who meet every four years to approve funding targets and new policies. The voting power of IDA member countries is based on their total of country donations, thereby continually providing the US with a veto within IDA. The IFC borrows money on the private markets to on-loan to private sector as partners in development; IFC is required to make a profit on these “investments”.

Transparency

The World Bank, like the IMF, should be modeling best behavior for its member-countries in all areas of governance, but especially in transparency, where it frequently advises borrowing countries to adjust their own performance. The Bank’s own practice is uneven. The World Bank has become the standard setter with its open data platform policy. Conversely, access to archival documents is sub-standard, whether considering the ideal (prompt, comprehensive, multi-lingual and electronic), the performance of the World Bank or that of the US Federal Reserve Board. Moreover, the World Bank exempts virtually all of its corporate information from disclosure, including, information about its own direct vendors, senior managers’ financial assets, procurement, contracts. Ironically, a number of the serious scandals affecting the Bank in recent years have involved its corporate operations.

The Bank Information Center (BIC), a non-governmental organization in Washington, tracks public access to World Bank documents.Regarding the Bank’s current Access to Information Policy, BIC finds that “it continues to limit public access in a number of serious ways:

- Overly Broad Exceptions: While the new transparency policy does recognize a presumption of disclosure, the exceptions are too broad. This is particularly true for the provisions pertaining to the deliberative process, third-party information, and Executive Directors’ communications.

- Public Interest Override Has Limited Application: The Bank successfully established a public interest override for information requests, but the override only applies to information restricted by only three of the ten exceptions.

- Opaque Board Meetings and Board Communications: The new policy does not call for open board meetings and rejected timely access to meeting transcripts and Executive Directors’ statements.

- Weak Simultaneous Disclosure Provision: All draft information considered deliberative is not subject to simultaneous disclosure. Countries can veto simultaneous disclosure and there is no commitment to disclose draft Country Assistant Strategies, which outline the Bank’s long-term development goals for a country.

These limitations in the new policy lead civil society observers to restrain judgment until practices change.

BIC concludes the Bank must “embrace [a] transparency culture” targeting citizens and affected communities so that they may take on an increased role in the development process. The Bank must consider that among the various stakeholder groups, affected people are the hardest group to reach. Thus the Bank must continue to develop initiatives to engage affected communities.

Inclusiveness

The World Bank has the same constituency arrangement and vote distribution as the IMF, with its corresponding strengths and weaknesses. In 2010 the World Bank Executive Board introduced a major advance with the addition of a third seat for Sub-Saharan Africa. Regrettably, the three largest economies of the region (South Africa, Nigeria and Angola) claimed the seat as their own, leaving the other two African EDs still representing in excess of twenty countries each.

Within the Executive Board, there is a dramatic imbalance between developing countries (the borrowers, or Part II countries) and the advanced economies (the donors, or Part I countries) and correspondingly serious tensions because of the real politik operating beneath the surface but shaping formal decisions and practices.

Many Executive Broad policies are determined in the IDA Deputies meetings every three years. Over the past decades, civil society organizations (CSOs) have used this framework to advocate for safeguard mechanisms for displaced persons, indigenous peoples and the environment. But emerging market economies (EMEs), those straddling the donor-borrowing divide, have come to resent these safeguards as unnecessary intrusions on their sovereignty that add costly delays and complexities to World Bank loans. Further, the IDA replenishment negotiations do not include EME Deputies even though significant shares of IDA resources have come from interest payments made by EMEs on IBRD loans. Those interest rates could have been reduced, saving the EMEs money, instead interest payments support LICs through IDA and cover the majority of the World Bank administrative costs, all without any corresponding credit in terms of voice and votes for EMEs on IDA decisions.

Serious unresolved participation issues for World Bank governance also extend to the roles for Parliaments, especially in borrowing countries, and for civil society whether from the “North” or the “South”. If World Bank policies, reflecting the priorities largely of Part I countries, and the practice of borrowing governments fail to protect vulnerable citizens or the common good (e.g., the environment), then what options do affected peoples and the global public have to protest and protect their countries? In turn, the EMEs insist that the inevitable tradeoffs such as those between the needs for growth (e.g., water issues and electricity generation) and survival of endangered species should be theirs to make exercising their right of eminent domain.

These tensions are in the forefront of the World Bank’s current (July 2012-June 2014) review of it safeguard policies. The Bank’s process for consulting on these policies is well-designed. The external stakeholders include “representatives” of borrowers, UN agencies, multilateral and bilateral development agencies, the private sector, foundations, universities and think tanks, labor, indigenous peoples, affected communities and various levels of civil society organizations. The question for future analyses is the quality of feedback to stakeholders, including the impact of these entities on outcomes.

Accountability

The World Bank’s Articles of Agreement draw a clear line of internal accountability within the Bank: staff are accountable to management, management to the Board, and the Board to the Governors. However this clear line only operates in practice between staff and management. The gravest institutionalized problem with World Bank is that actual power resides in the G7 countries, and increasingly with the G20. The President is chosen by the United States, with the rest of the G7 having the power to strongly oppose. The President is then answerable, de facto, to these external powers, not to the Board.

Each time the new World Bank President is to be chosen commitments are made all round the world that this Presidential selection process will be merit-based alone and nationality-blind. And each time, the White House proposes and the rest agree. The deal is done. In the last selection process, the Board interviewed two eminent Southern Candidates: Jose Antonio Ocampo of Colombia and Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala of Nigeria. Of course the US candidate, Jim Kim, was selected. This selection process has endured for 60+ years, and no US President (nor European leader vis-à-vis the IMF) is willing to take the domestic political heat for “losing” the World Bank Presidency.

The Executive Board itself is accountable to no one. The Board of Governors, neither as a whole nor through the Development Committee, does not evaluate the performance of the Board as a corporate entity nor of the individual Executive Directors, nor of the Bank’s President.

Responsibility

The Executive Board, management and staff all pay close attention to project preparations. However, once the Board approves a project loan, the Bank only checks progress in terms of release of funds. Staff promotions continue to be closely tied to “amount of money out the door.” Corruption or shoddy work or any similar action is likely to go unreported, noticed only upon project completion or if loud public attention is called to it during the course of project implementation.

The Bank does have mechanisms to register staff and affected peoples’ complaints. It has a Vice President for Integrity, and an “integrity app” to download to a personal phone, and mechanisms for guaranteeing privacy. However, in the lead up to the resignation of former Bank President Wolfowitz, these mechanisms were found to be severely lacking.

In design, the World Bank’s whistleblower protection policies are “state of the art.” But in practice these are only a “cardboard shield” since it does not allow access to external arbitration in retaliation complaints, and whistleblower protections therefore suffer from an institutional conflict of interest. Although a whistleblower may request external mediation, he or she must choose a mediator from a list pre-selected by the Bank.

Even this protection does not apply within an Executive Director’s office. All staff work at the pleasure of the ED, and anyone wishing to disclose corruption can report quietly to their own home government, or go to an outside organization such as the Government Accountability Project or GAP. In following either course, however, a whistleblower still risks summary dismissal and any future prospects at home, at the Bank or in the IMF.

The World Bank was the first international financial institution to organize an Inspection Panel to receive and investigate complaints directly from adversely affected individuals. The Panel reports directly to the Board, not to management. Complaints must come from a group (minimum of three people) seriously and negatively affected, or about to be seriously and negatively affected, by the World Bank’s failure to follow its own procedures, and while the project is not yet completed. To date, the Inspection Panel has not received complaints related to non-project lending. The Panel cannot provide restitution or recompense for harm already done.

The Independent Evaluation Group (IEG), formerly the Operations Evaluation Group, now reports directly to the Executive Board through the Board Committee on Development Effectiveness. Management of the World Bank (IBRD and IDA), IFC and MIGA can neither censor nor delay IEG studies. This author could find no assessment of the extent to which the World Bank, IFC and MIGA implement IEG recommendations. IEG undertook an extensive self-evaluation in 2011 but Johannes Linn, a former World Bank Vice President for Europe and Central Asia and now a Non-resident Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution, identified several gaps in the self-evaluation which might have been corrected through an independent external evaluation, such as those the IMF conducts on its own Independent Evaluation Office.

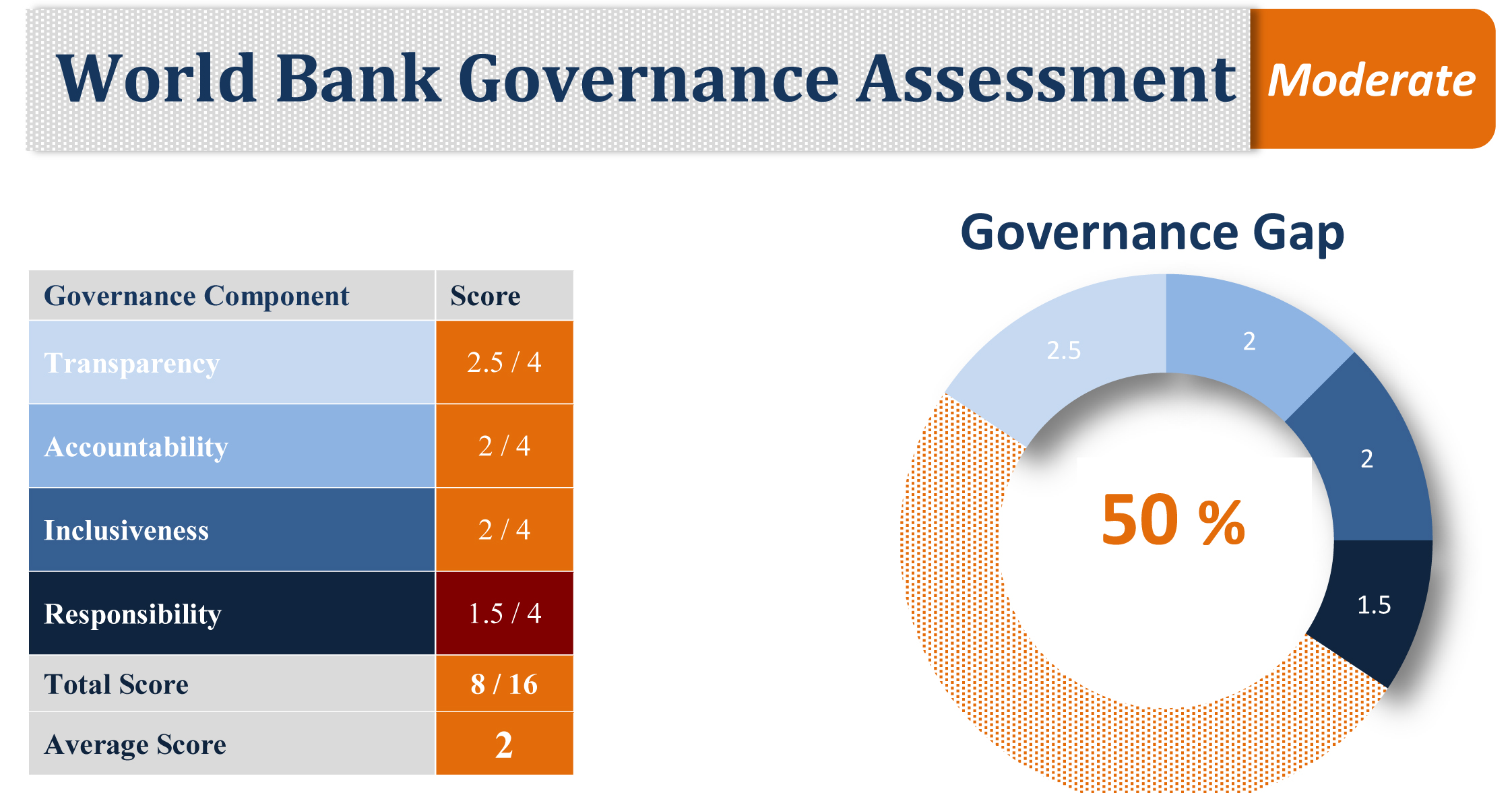

In summary, the World Bank is well on its way to good performance on Transparency (2.5). For Inclusiveness, the Bank shares the strengths and weaknesses of the IMF, namely all member states are represented but the Eurozone is over-represented, and in IDA calculations the IMF is over-represented; with affected peoples and Parliaments sorely absent (2). The Accountability is modest, with the bottom of the bureaucracy answerable to their superiors, and rewarded for the outflow of funds, but the Executive Board is answerable to no one. Further, internal whistleblowers receive no effective protection (2). On Responsibility, the World Bank took a major step forward with the establishment of the Inspection and with the greater independence of the Independent Evaluation Group. However, while the Inspection Panel may improve future Bank behavior, it can offer no compensation to negatively affected people. For the IEG, not even a mechanism to track implementation of its recommendation (1.5).

World Bank Impact

Author: Matthew Martin, Development Finance International

Introduction

According to the World Bank, its overarching mission is “a world free of poverty”. The Bank fulfills these goals by providing i) loans, interest-free credits, and grants to developing countries to support a wide array of investments in education, health, public administration, infrastructure, financial and private sector development, agriculture, and environmental and natural resource management; and ii) policy advice, research and analysis, and technical assistance/capacity-building to developing countries. Development research and statistics support its work. This assessment of World Bank impact places particular emphasis on low-income countries (LICs) (though it also lends to virtually all middle-income countries).

World Bank loans and grants for LICs come largely via the International Development Association (IDA), which is funded by a combination of donor contributions, repayments of past loans, and World Bank Group net income from other loans and investments.

In what follows, the World Bank is assessed on the adequacy of its resources and the way in which they are allocated; on its policy and impact on poverty and inequality (its main mission and goals); its policies on various sectors and cross-cutting themes; its record of delivery including conditionality; and its private sector activities.

Resources & Allocation

World Bank funding overall is very large – for example making it the largest global funder of education, HIV/AIDS and water and sanitation projects – having peaked at US$58.8 billion of commitments in 2010 (responding to greater country need as a result of the global economic crisis) before falling back to US$31.6 billion in 2012. Its IDA resources are much lower, at USid=”mce_marker”6.5 billion a year. Though they were increased by 18% for the last three year replenishment period covering 2012-14, they look unlikely to rise significantly in the next few years given cuts in OECD aid budgets: indeed the latest IDA replenishment discussions have agreed a real stagnation or fall. Nevertheless, IDA remains a major actor in official development financing across the world (around 20% of multilateral flows or 10% of total flows) and could therefore have a strong potential influence on setting new rules for development finance.

LICs would like to see IDA funding levels rise significantly given massive MDG financing needs (though they also have major criticisms of how IDA funds are allocated and delivered as discussed later in this section), and therefore perceive IDA funding as inadequate. They have made several proposals for more flexibility in using World Bank funds, with greater use of IBRD (or combined IBRD and IDA) money for high-return infrastructure projects rather than their current focus on “enclave” high-return natural resource projects. They also oppose any hardening of lending terms of IDA recipients, which looks likely to be agreed as part of the latest IDA replenishment. CSOs are somewhat divided on whether IDA should have more resources, with most preferring higher funding for UN agencies and regional development banks, especially in relation to climate change.

The second main problem perceived by LICs and CSOs with World Bank resources is the system through which they are allocated. This has been based largely on country “performance” as assessed through the Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA), which has been heavily criticized for making the Bank much less able to respond to country needs in terms of low human development or high poverty, or to the particular circumstances of countries which are more vulnerable to economic or climatic shocks, or emerging from conflict or in other fragile situations. These characteristics of the CPIA will become increasingly problematic in future years as many non-fragile and less poor countries graduate from using IDA funds, leaving a very high percentage of its funds going to higher need, more vulnerable, “lower-performing” countries.

As a result of these factors and the delivery issues discussed in Issue 3 below, IDA flows to fragile and conflict-affected states have stagnated over the last 10 years, even though they have become a more important proportion of the beneficiary countries. IDA 17 intends to tackle this problem with a five point reform agenda to increase its effectiveness in fragile states, and higher allocations to these countries in 2014-17.

The CPIA has also been criticized for the lack of transparency and subjectivity of its country ratings, and for the detailed content of its rating system, including many criteria which appear to take little account of environmental, inequality/equity, or decent work objectives.

An additional problem has been seen by LICs in sectoral allocation – especially the lack of sufficient funds for regional “transformational” infrastructure projects. This has been a particular focus of African governors of the World Bank, and such financing has already been increased slightly with 10 priority projects in energy and agriculture launched in 2012. Funding for such transformational projects will probably be scaled up slightly during 2014-17 in the new IDA replenishment. On the other hand, CSOs have been opposing a greater focus on large-scale infrastructure; especially if it is at the cost of social sector investments or delivered through PPPs (see also Issue 3 below). They have been instead urging IDA to spend more on health and nutrition, and the Bank to make universal free health care a primary goal.

Policy Impact on Poverty & Inequality

The Bank has long been criticized for not placing enough emphasis on directly combating poverty and inequality, and seeming to rely on an assumption that income will “trickle down” to the poor via accelerated growth. However, the Bank has recently reinterpreted and reinforced its interpretation of its mission as being to “virtually end extreme poverty in a generation” (because this will take time and 3% of poverty will be impossible to end due to exogenous shocks); and to “push for greater equity” by using a new “shared prosperity indicator” to ensure there is income growth for the bottom 40% in each country.

Many in civil society and developing countries have criticized the Bank for a lack of ambition in these goals – for tackling only “extreme poverty” (income of below USid=”mce_marker”.25 a day) rather than poverty more broadly defined (e.g. below US$2 or more); and for failing to measure progress to shared prosperity more comprehensively through inequality indicators such as Gini or Palma. They have also criticized the Bank for ignoring a rights-based approach to development, and are worried that drafts of the Bank’s strategy for attaining the goals imply excessive reliance on growth and private-sector led development.

However, others have welcomed the Bank’s new focus on inequality and shared prosperity which was not among its previous goals. They see it as potentially a major step forward in focusing on outcomes instead of only equality of opportunity in terms of access to markets, resources, and an unbiased regulatory environment and individuals”. In addition, these goals look likely to be in line with those to be adopted in a UN post-2015 global development framework.

It is extremely hard to assess World Bank impact on poverty or inequality. Unlike the IMF, it has been very little involved in designing the macroeconomic framework in LICs in recent years, and lends to virtually all LICs, so it is not possible to ascribe major macroeconomic impacts to World Bank projects or to compare countries with and without World Bank programs. However, the Bank in common with the broader donor community has seen acceleration of growth and reduction of poverty in most LICs, but much less progress on inequality. It has also conducted very little in-depth analysis of how its policy recommendations, programs and projects are impacting on these issues – and will need to scale up such analysis dramatically.

It is intended under division of labor agreements with the IMF that the World Bank should play a key role in such aspects as the distributional consequences of tax and spending policies, as well as providing policy advice on social protection, job creation and financial inclusion to fight against inequality. The Bank acknowledges that these have not been at the center of its policies and intends to scale up focus on them in the next few years, as also stressed in the World Development Report 2013

Policies on Sectors & Cross-Cutting Issues

Social and Environmental Policies:LIC governments and CSOs have welcomed the renewed commitment to universal education and health care by the new Bank President during 2012-13, and some of the President’s own speeches in which he emphasized that user fees for such services should be eliminated or minimized to avoid excluding the poor. However, CSOs and education/health experts have been highly critical of some proposals made by the Bank for delivering these goals through the private sector, on the grounds that they are typically less cost-effective and exclude the poorest, undermining equity and rights to education and health.

The Bank has been seen by LICs and CSOs until recently as insufficiently committed to combating climate change in its actual lending policy, continuing to make large investments in fossil fuels and not routinely assessing its projects and programs in depth for their potential impact on climate change. However, this appears to have been changing somewhat in 2013, with much greater focus on mainstreaming climate change, disaster risk management and low-carbon development in IDA countries, and an announcement that it will in general avoid financing coal projects.

There is generally seen to have been some progress on “gender mainstreaming” and monitoring gender impact of Bank projects over the last decade. However, there is not nearly enough analysis of gender impact of country strategies and operations, or emphasis on measuring the achievement of project gender equality objectives and collecting gender disaggregated data. In addition, the Bank needs to do much more on maternal health care, on women’s economic empowerment, and on gender-based violence, and to make its policies, strategies and projects respond to women’s needs and rights, especially in providing high-quality jobs.

Delivery & Conditionality

Another key question is whether the World Bank is delivering its mandate efficiently and in line with global agreements on what constitutes “effective aid”. In other words, to what degree is it living up to new agreed rules for global development finance in the way it delivers its funding?

Recent assessments by low-income countries indicate IDA performs well compared with other multilateral development financing institutions in terms of

- Channeling its assistance via the recipient government budget;

- Aligning its assistance with priority sectors and programs in national development and poverty reduction strategies;

- Programming commitments and disbursements over a multiyear period;

- Untying its assistance from any link to exports of individual countries; and

- Being fully engaged in national and sectoral policy dialogue with countries.

However, it performs less well in terms of:

- Low quality and capacity-building content of much of its technical assistance;

- Complex and slow disbursement and procurement procedures;

- Failure to channel its support via government public financial management and procurement systems, or to use government-led results tracking systems; and

- High levels of policy and procedural conditionality which delay disbursements. IDA has been making some recent efforts to streamline procedures and reduce delay, including through greater use of national procurement systems, and decentralization.

Most Bank programs and projects have some form of policy conditions attached to them, but this is most prevalent in “development policy loans” (DPLs) – which have fallen from 25% to only 12% of IDA lending in recent years. The Bank has somewhat reduced the use of policy conditionality in recent years, in particular reducing duplication with IMF macroeconomic policy conditions. However, a 2012 internal review of DPLs found that operations still contained 10 “prior actions” before funds could begin to be disbursed. Concerns also remain among LICs and CSOs about the use of ‘one size fits all’ conditionalities remain, restricting the pursuit of democratically chosen policies appropriate to national contexts; and about the Bank’s lead role in the formulation of extremely lengthy conditionality matrices which guide budget support disbursements by multiple donors in many countries.

LICs also found IDA to be only average in terms of its flexibility to respond to economic or climatic shocks, including during the global economic crisis of 2009-11. Extensive discussions among donors and recipients about how to improve this aspect of its performance resulted in the creation of a more flexible Crisis Response Window in 2012, but this has not been used much, has yet to be tested by a major global crisis affecting LICs, and looks likely to be set at only 3% of IDA resources for the 2014-17 period (which would probably be an inadequate response to major crisis).

Overall, LICs have assessed IDA as performing less well than the better-delivering UN agencies on both policies and procedures; and worse than the EU and regional multilateral development banks on policies. These assessments are consistent with those conducted under the evaluations and surveys of donor compliance with the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness in 2008-11.

Private Sector Engagement & Lending (IFC)

A final way in which the World Bank might be expected to be creating new rules for global finance is through its engagement with the private sector, principally via its private sector lending arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC). This is particularly important given that one primary goal of IDA’s strategy for the next few years is to “leverage” greater private sector resources for development given that its own funds will be stagnating or falling in real terms.

LICs have repeatedly recognized that the World Bank’s provision of private sector support is useful and countries have benefited from IFC instruments. However, they have indicated that IFC has not been as good at policy or delivery as IDA: in particular, IFC facilities have tended to be tailored towards countries with better capacity to access the funds, and there has been minimal differentiation of interventions according to country circumstances. There has also been overconcentration on highly profitable sectors such as mining, petroleum, tourism and finance, as well as a tendency to partner with large transnational investors. CSOs and independent analysts have also pointed to its very limited impact on poverty.

The Bank’s assessment of private sector “investment climate” through the “Doing Business” report, which underpins many of its private sector investments, has also been highly criticized by civil society for its focus on reducing taxes and promoting “flexible” labor markets by minimizing labor regulations. This publication is to undergo a fundamental review in 2013-14 including consultations with LICs and CSOs.

There has also been strong criticism from CSOs of the IFC’s growing move into public-private partnerships or private financing for what have previously been mainly publicly-funded infrastructure and social sector investments. This is presented as logical given shortages of public funding and massive infrastructure needs, and follows leadership given in G20 communiqués on efforts to increase investment financing, which has caused similar trends in all development financing institutions. However, these types of projects are much more expensive than public sector funding such as bonds, and are even being extended in a growing number of cases to health, public or low-cost housing, and education. The 2012 IEG report on the “Results and Performance of the World Bank Group,” showed that Bank effectiveness was lowest in infrastructure and public-private partnerships.

IFC has also been criticized (including by the World Bank ombudsman) for its failure to track the environmental and social impact of its interventions, notably those which operate indirectly via financial intermediaries such as banks and investment funds. This is because it relies on client self-monitoring and self-assessment, and very limited reporting, way behind some other lenders to the private sector including the Asian Development Bank and US Overseas Private Investment Corporation, and is seen as a much weaker system of social and environmental safeguards than those of the World Bank itself. One area highlighted recently has been the failure of such safeguards to prevent “land grabs” from LIC citizens with little or no consultation, resulting in a commitment from the Bank to use stronger guidelines in this area. CSOs have therefore been particularly worried in 2013 that the World Bank has been conducting a consultation on its safeguards policy with one possible option being that safeguards might be revised to match those used by the IFC.

A final area in which the World Bank has not taken significant action is in maximizing tax collection for LICs through its investments. It could for example insist that it would not do business with corporations which are based in tax havens, or are failing to report all their accounts disaggregated by country, or are failing to pay full tax in host countries on projects they are executing with IFC funding. Overall, the World Bank seems to be doing little to promote new rules for private finance.

Overall Assessment

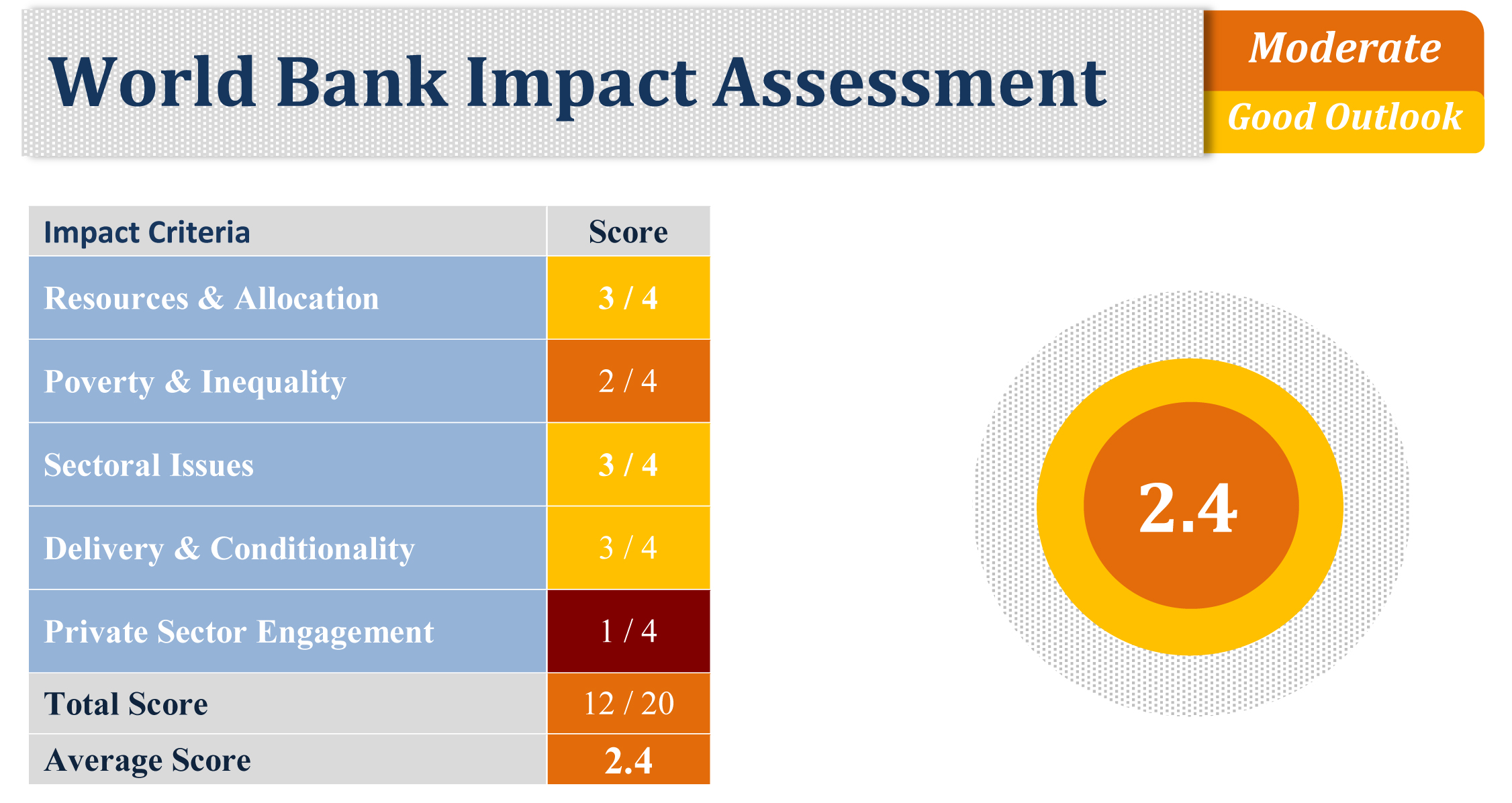

The overall assessment of World Bank impact should be seen as: Insufficient resources and poor allocation (though with efforts by management to fight for more resources and make some improvements in allocation [3]; Progress on goals but unclear on impact on growth and poverty reduction, inequality and inclusion, and pro-poor spending/tax/labor [2]; Progress but continuing problems/doubts on education, health, climate change, gender [3]; Progress but continuing concerns on delivery, conditionality and flexibility [3]; Poor and showing few signs of improvement on private sector investments [1].

Case Study: Impact of World Bank Policy and Programs in Egypt

*This is a summary ofMarch 2013 study by the Bank Information Center and the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR), researched and written by Yahia Shawkat.

Despite billions of Egyptian pounds in infrastructure investment both from national and international sources, Egypt’s cities, towns and villages continue to grow and function in much the same way they have over the last three decades, namely through self-reliance. There are varying degrees of deprivation such as shortages in housing, municipal services and transport –the three main ingredients of functioning communities — while on the other hand, a minority is very well served. It is no surprise then that the main call of the January 25th revolution was “Bread! Freedom! Social justice!”

One significant partner the Government of Egypt has had in the development of Egypt’s built environment has been the World Bank, which has invested heavily in infrastructure projects such as electricity, waste water and natural gas, as well as in transportation and affordable housing. These investments come along with the Bank’s policy recommendations and technical assistance which have included championing private sector involvement and phasing out government subsidies, while taking the stance that government should be an “enabler” rather than a “provider” of such services.

In July 2012, the Bank’s portfolio of built environment-related projects was $3,180 million, roughly 81 percent of the total $3,945 million portfolio of active WB projects in Egypt. This long-term interest in Egypt puts the World Bank in a position to shoulder some of the responsibility for the state of the built environment in Egypt.

Why has the large amount of foreign and national funding not succeeded in solving or substantially addressing the many built environment challenges faced by Egypt’s citizens? Have the Bank’s efforts played a positive role in promoting pro-citizen built environment policies and projects? Analyzing the World Bank’s Egypt 2006-2009 Country Assistance Strategy (CAS), which was extended until May 2012, provides answers to these questions. The strategy’s main objectives were; facilitating private sector development, enhancing the provision of selected public goods, and promoting equity. The CAS is also analyzed in light of the Bank’s investments in policy programs and development projects during the same period.

On developing the private sector and in using the PPP model: While the 2006-2009 CAS finds that the “GoE is conscious of the need to ensure resulting [privatization] arrangements do not create private monopolies and that they are embedded within a regulatory and supervisory framework that protects the public interest,” it is clear from the way the solid waste management sector has performed since it has been formalized that there is a need for greater focus on regulation.

On regional disparities: Only a comprehensive built environment policy, along with representative local government, will balance regional disparities and promote the equitable distribution of services and investments, something that the 2006-2009 CAS largely failed to achieve and where investment remained highly centralized in the Greater Cairo region.

On stakeholder consultation:The lack of true representation and consultation of stakeholders was another area in which the 2006-2009 CAS was weak. “Stakeholder participation” in the CAS was largely limited to central government and private sector affiliates, rather than including a broader range of affected stakeholders. In order for a comprehensive built environment policy to be formulated, local community participation must be mainstreamed into both the policy development and project development frameworks.

On promoting equity and the poor: Just less than a quarter of the WB portfolio of investments was themed as “urban services for the poor”, and even then the “poor” were not well defined. For example the Affordable Housing Mortgage program’s target was middle and lower middle income groups – between the 75th to 45th percentiles – and not the low income groups.

On involuntary resettlement: Half of the 14 built environment-related projects triggered the Bank’s involuntary resettlement safeguard policy, indicating that there was a risk of people being displaced from their lands, homes, or livelihoods as a direct or indirect result of the project.

Taking an in-depth look at the 2006-2009 CAS has demonstrated several areas in which the World Bank in coordination with the GoE failed to address the true needs of Egypt’s citizens in the built environment. In the coming 18 months of the Bank’s new interim strategy, there is a great opportunity for the World Bank and the Government to work with citizens and all stakeholders to develop a comprehensive plan for the built environment. This will in turn help to guide the Bank, GoE, and stakeholders in the development of a new, post-revolution CAS that will reflect the needs of the built environment and the Egyptian citizens who have kept it running for the past several decades.

The full text of the study can be found here

The report can be accessed through the attached link: